Why we need re-founders

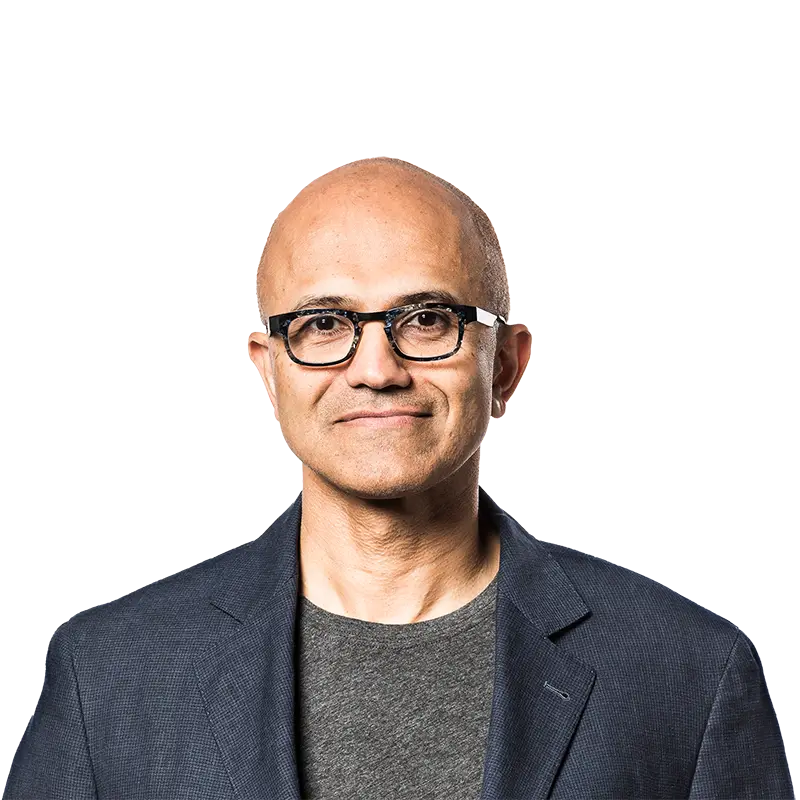

To achieve massive scale, you don’t just need founders, you also need a re-founder – someone to come in at a later stage to keep the mission and culture on track. As Microsoft’s third CEO ever – after Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer – Satya Nadella is doing just that. He discusses how he has transformed Microsoft from a cutthroat culture towards embracing social networks, collaboration, and cloud.

To achieve massive scale, you don’t just need founders, you also need a re-founder – someone to come in at a later stage to keep the mission and culture on track. As Microsoft’s third CEO ever – after Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer – Satya Nadella is doing just that. He discusses how he has transformed Microsoft from a cutthroat culture towards embracing social networks, collaboration, and cloud.

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Do you want to be CEO of Microsoft?

- Chapter 2: Companies need founders — and re-founders

- Chapter 3: The insider’s outsider

- Chapter 4: To hit refresh, go in search of passion and commitment

- Chapter 5: When poor culture gets in the way of good decisions

- Chapter 6: Advice from Steve Ballmer: Be yourself

- Chapter 7: Leadership change at "Veep"

- Chapter 8: To refresh a culture, you've first got to earn it

- Chapter 9: Why Satya Nadella abolished stack ranking

- Chapter 10: Microsoft takes a fresh approach to acquisitions — including LinkedIn

- Chapter 11: How do we earn the right to play a big role in society?

Transcript:

Why we need re-founders

Chapter 1: Do you want to be CEO of Microsoft?

SATYA NADELLA: If you’d asked me even the day before or the hour before, I would have said, “Hey, there’s a chance, but I don’t know who was interviewing, who wanted the job.” There was a lot of, I would say, intrigue around it.

REID HOFFMAN: That is Satya Nadella. And he’s talking about the moment in 2014 when it seemed he might become the next CEO of Microsoft. Satya had been with the company for more than 20 years. But even down to the last minute his promotion was far from certain.

NADELLA: I remember where one board member asked me, “Do you really want to be a CEO?” I said, “Only if you want me to be the CEO.” And then he said, “Well, that’s not how CEOs are made, right? I mean, CEOs want that job.” And I said, “But that’s how I feel.” I remember talking to Steve about it.

COMPUTER VOICE: Steve Ballmer, Microsoft’s second CEO.

NADELLA: Steve turns to me and says, “Yeah, it’s too late to change. You are who you are.”

HOFFMAN: Satya was, in fact, very different from either of Microsoft’s previous CEOs, especially the one he’d be replacing.

Where Steve Ballmer projected absolute confidence and assurance, Satya prioritized asking questions. Where Steve saw the job as leading strongly from the top, Satya saw it as building a more open conduit for ideas. He wanted to be the kind of CEO that would make room for feedback, and foster a culture that rewards new ideas.

But as different as Steve was from Satya, Steve was also the one who advised him to be himself.

NADELLA: The best advice I even got from Steve at one point was just “Be yourself, right? You’re never going to be me. So, therefore, don’t try to fill my shoes.”

HOFFMAN: As you probably know, Satya got the job. And he took Steve Ballmer’s advice to heart.

NADELLA: Recognize first that I’m not a founder, obviously. Bill and Paul founded the company. Bill and Steve built the company. So, Steve had founder status as far as I’m concerned. I felt like, “Oh, I just can’t be like, ‘Okay, here’s the third guy who just shows up and does what Bill and Steve did.'” It needs a full reset. The reset meant I needed to make both that sense of purpose, mission, and culture first class, and my own.

HOFFMAN: I would actually argue that Satya has run Microsoft as a type of founder. You can call it being a “re-founder,” or even a “late stage cofounder.”

The late-stage co-founder doesn’t need to have been there “in the garage” from day one. And they don’t have to be the CEO, although the CEO often has the most leverage to effect change. What they need is the ability to tease out and articulate what had previously just been implied.

NADELLA: I went through Microsoft. We would talk about culture, but it is never a serious thing. So, I felt like, “What’s the meme to even pick, so that we can even have a rich conversation on it?”

HOFFMAN: Satya not only started that rich conversation about culture and mission, he made it central to his leadership. And that helped Microsoft kickstart a new phase of growth that continues to this day.

That’s why I believe companies don’t just need founders… they also need re-founders. As businesses scale, re-founders keep mission and culture on track, and responsive to a changing world.

Chapter 2: Companies need founders — and re-founders

HOFFMAN: I’m Reid Hoffman, cofounder of LinkedIn, partner at Greylock, and your host. And I believe companies don’t just need founders… they also need re-founders. As businesses scale, re-founders keep mission and culture on track, and responsive to a changing world.

Imagine you’re at your computer, working late at night on a presentation. You’re scanning an article on emperor penguins to find the perfect quote about perseverance. When suddenly, it happens: The screen becomes unresponsive. The scroll bar won’t scroll. The page is frozen.

What do you do? Well, thanks to the efforts of thousands of programmers since the dawn of the Internet, you probably already know the solution. You just click the circular arrow icon in the corner, and hit refresh. The article reappears, you select your slice of penguin-themed wisdom, and carry on.

The page you refreshed contains the same information as before, but now it’s functional. It’s a way to start again, without starting over.

This is a brilliantly simple metaphor for leadership. Organizations, too, can be sluggish and unresponsive, until you hit “refresh” on things like mission and culture. And by the way, I wasn’t calling my own metaphor “brilliant.” I’ve actually borrowed it from our guest.

I wanted to talk to Satya Nadella about this idea of resetting culture because of how successfully and thoroughly he’s done it for one of the most scaled organizations in the world. As CEO of Microsoft, only the third in its history, he has shifted the company’s focus away from a cutthroat culture and anticompetitive practices towards embracing social networks, collaboration, and cloud.

His book – called, appropriately, Hit Refresh – crystallized ideas about how to kickstart a stagnant culture for the good of employees, and the world they serve. And since he wrote that book in 2017, Microsoft’s success has only elevated. In June, the company hit $2 trillion in value.

But you don’t have to be a CEO to trigger a refresh in your business. And you don’t have to be new to a company.

Chapter 3: The insider’s outsider

NADELLA: I always say I am an insider with an objective outsider perspective.

HOFFMAN: Satya was born in Hyderabad, India, and came to the U.S. to study computer science, earning a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 1990. He started his career at Sun Microsystems, but it wasn’t long before Microsoft came calling.

NADELLA: I was at Sun, and I was planning on going to business school. That was the trajectory I was on. And then I got an offer. And I was convinced that look, you ultimately want to leave business school and come back here. So, why don’t you come here directly?

HOFFMAN: So Satya went to Microsoft. And he loved it.

NADELLA: The thing that struck me, I remember, each week, I would see a new category created, right? One day, it will be Access. The next day, it will be Publisher. The next day, it would be a new release of Visual Basic.

I mean, it was just so exciting to see the creativity of the developers, whether they were internal or external.

HOFFMAN: Microsoft wasn’t a brand-new company. Bill Gates and Paul Allen had founded it some 17 years earlier with a mission to put “a computer on every desk and in every home.” But with so many software product launches, one after the other, it still felt like a startup. Speed of growth is often its own enthusiasm-driver for employees. Because at that stage, speed can be a key part of the mission. And Microsoft was growing exponentially.

But Satya wasn’t in the buzzy part of the business, at least back then.

NADELLA: I joined what was at that point the fringe of the company, which was the server.

For most of the ’90s, I would say, Reid, we were still in the basement of building out that enterprise credibility. I remember, distinctly, going to New York City, visiting all the banks, and in particular Goldman Sachs. They made me wait in the waiting room and say, “Hey, who is this guy from Microsoft wanting to talk to us about servers?” They thought of us as some toy PC maker.

HOFFMAN: As Satya sat in the Goldman Sachs waiting room, he thought about the reasons why Microsoft was so successful in the pro-sumer market, while still struggling to assert legitimacy with enterprise clients.

NADELLA: It takes long-term commitment, in particular, for enterprise sensibility for what was predominantly a consumer company, because it goes back to trust. It’s not just technology. I see that hubris sometimes in some of the folks here. “I have technology, I’m so smart. So, therefore, the world should come and pray at my altar.” That’s not the way commercial customers want you to even show up.

HOFFMAN: That hubris Satya observed would increase with time, even between departments, as he moved up the ranks at Microsoft. It was now the mid 2000s, and Microsoft was operating under its second-ever CEO, Steve Ballmer.

Chapter 4: To hit refresh, go in search of passion and commitment

NADELLA: One day, Steve comes to me and says, “You know what? I’ve got an assignment for you. I think you should go run Bing.”

HOFFMAN: You know Bing. It’s Microsoft’s search engine – then the one that wasn’t the other one.

NADELLA: At that time, it was not even called Bing. It was called Live Search or what have you. We had had a lot of attrition. Obviously, Google was the behemoth even back in that time.

I had to make a decision. So, I went to the parking lot. I drove past the building. It was 8:00 or so in the night. At that point, the reputation of the team, the attrition, all of that was a bit of a challenge, but I saw people were working late in the night. I said, “What the heck are these people doing here?” So, I remember parking, walking around. I just saw all of these folks who were super committed. I said, “God, I got to join this party.”

HOFFMAN: In that moment, Satya saw the Bing team’s enthusiasm and sense of mission. It reset his expectations for the division, and what was possible.

This is a great example of the power individuals have within a company to hit refresh even if they aren’t in leadership roles. By doubling down on their commitment to the mission, each member of the Bing team had an impact on each other member. And collectively they stirred a greater sense of possibility in their new team leader. This is how good culture spreads – with each person having the ability to affect it.

But as that’s how good culture spreads, that’s how poor culture spreads too.

Chapter 5: When poor culture gets in the way of good decisions

NADELLA: I’ll never forget this. When I was leading Bing, Bill, at that point, he was the Chief Software Architect. He called a meeting, maybe 2009.

HOFFMAN: Bill Gates had called the meeting to prepare the team for an upcoming acquisition.

NADELLA: Our server division was about to acquire a piece of technology basically for parallel data warehouses. Inside of Bing, we were building up essentially, the infrastructure for our data parallel workload, which is essentially a search engine.

HOFFMAN: In other words, Microsoft was about to buy something that Bing was already doing.

NADELLA: I remember going into that meeting along with a couple of other lead engineers from Bing and sitting across the table from this other group that was solving what was the enterprise data warehouse problem as understood. And then here, we had essentially the same thing but done in a very different way.

HOFFMAN: Satya’s about to get technical here. He realized in that moment how Microsoft could use Bing to accelerate their cloud service platform, Azure, to rival Amazon’s version, AWS.

NADELLA: That is the moment that I think it struck me that what Amazon was doing on the other side of the lake, the idea of as a service infrastructure and the elasticity, but more than just the business model shift, this unit of scale being completely different is what dawned on me. In fact, that is one of the things I look back and say, why didn’t I, at that point, say to Steve or Bill, “You know what? It’s time to fold the Bing infrastructure in order to accelerate Azure.”

But yet, I didn’t act, right? I mean, that is a real issue, which is what happens in a large enterprise, even for a senior executive who sees it but doesn’t act?

HOFFMAN: Why didn’t Satya act? He saw that Bing could be used to support Azure. No new acquisitions needed. He saw it. So why not speak up? Satya has a theory.

NADELLA: To some degree, it requires both sides. Yeah, I should have been bolder in that role to say, “Hey, I see this. I want to advocate for it.” And then on the other side, the people who are leading our server side would need to have had a growth mindset. Because at that point, they viewed us as Bing, as, “Hey, you’re the loss-making division of Microsoft, so I don’t have time for you.” That is where culture in some sense gets in the way of wisdom prevailing.

HOFFMAN: Even in that moment of failure, Satya learned something important. Poor culture did get in the way of wisdom. The leaders in the room might not have shot down Satya’s comment. But they also didn’t incentivize him to make it.

A growth mindset thrives on the diversity of ideas, good and less-good. Meanwhile, a culture that says, “We don’t have time for any bad ideas, so let’s just keep moving!” is missing out on transformational ones as well.

Changing this part of culture usually falls to the leadership team. But it doesn’t have to. If you’re in a position like Satya, where you can see something that everyone else is missing, you can speak up.

It can be a bit of a high-stakes play. But even if it’s not rewarded in the moment – in fact, even if it’s punished in the moment – you show yourself as someone who puts positive energy toward the company’s mission. That’s an impulse good managers reward.

Satya took this lesson with him as he climbed the ladder at Microsoft… all the way to the day he was named CEO. You may remember the advice Steve Ballmer gave him, from the top of the show.

Chapter 6: Advice from Steve Ballmer: Be yourself

NADELLA: The best advice I even got from Steve at one point was just “Be yourself, right? I mean, you’re never going to be me. So, therefore, don’t try to fill my shoes.”

HOFFMAN: Satya knew he wanted to lead the company as himself. And he knew what he wanted to prioritize.

NADELLA: I felt like, “Oh, I just can’t be like, ‘Okay, here’s the third guy who just shows up and does what Bill and Steve did.'” It needs a full reset. I felt that the reset meant I needed to make both that sense of purpose, mission, and culture first class, and my own.

[AD BREAK]

HOFFMAN: We’re back with Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella. We’ve been talking about the ways a leader, or in fact anyone in an organization, can hit the refresh button and reinvigorate stagnating mission and culture.

To share this episode with a friend, send them to mastersofscale.com/nadella. N-A-D-E-L-L-A. To hear my full, unedited conversation with Satya, become a member by going to mastersofscale.com/membership.

Hitting refresh is something that happens in all kinds of industries, not just in tech. So before we get back to Satya, let’s take a brief detour from Microsoft headquarters, to Hollywood… and the moment another leadership change was about to unfold.

Chapter 7: Leadership change at “Veep”

DAVID MANDEL: When I first got the call that Armando was going to be leaving, it was a bit of a shock. Just as a fan of the show, it was very much like, “Oh my God, wait a minute. Armando is leaving ‘Veep.’”

HOFFMAN: That was TV writer and director David Mandel. He’s known for his work on Emmy Award-winning shows like Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm … and, more recently, as executive producer of the fast-talking, foul-mouthed political satire Veep.

But David didn’t create Veep. That distinction belonged to the show’s original showrunner, Armando Iannucci. David got the call to take over as showrunner in Season Five. And he wanted to put the cast and crew at ease.

MANDEL: I start sitting down, having breakfast with the cast individually as quickly as I could. He will admit this. Tony was really worried.

HOFFMAN: That would be actor Tony Hale, who played Gary, loyal aide to the show’s lead character, Selina Meyer.

MANDEL: Tony was definitely the one that was just like, “Who is this guy, and why is he here?”

HOFFMAN: David needed to earn Tony’s trust, along with the rest of the team. But he also needed to make that team his own, which occasionally proved … challenging.

MANDEL: They made me hire three editors. And I was very confused.

HOFFMAN: Three editors, for context, is one more than David was used to. It took time to figure out why.

MANDEL: Armando shot a lot and often found the episodes in the editing room. And so the reason he had three editors was he would bounce from edit room to edit room as they were working. They were just constantly trying different things. I definitely do the show just differently. I like to know what the first scene of the season is going to be, and the last scene of the season’s going to be. I lay it all out on a giant board in a conference room, 10 columns, 10 shows. I’m not finding anything in the edit room.

HOFFMAN: Processes that had been set up for Armando didn’t make sense for David. But when he tried to change them, he was often met with a curious answer.

MANDEL: You’d often get hit with this, “It’s Veep.” That was always the answer. It’s Veep. Kind of, “This is how we’ve always done it.” And we did it that way for a year. And it drove us a little crazy, occasionally, the, “It’s Veep.” And then after one year, it was just like, “Yeah, I don’t care anymore.”

HOFFMAN: “It’s Veep syndrome” might feel familiar to anyone whose organization has gone through a leadership change. It can be difficult to shake loose old habits and established processes. But it’s also completely necessary.

MANDEL: If I had tried to do and write exactly Armando’s show, you would have gotten a weird knock off. I can write Veep, but I can’t do an impression of Armando. It just comes off like some weird bootleg, like a weird mimeograph, slightly smudged and purple and not quite as good.

HOFFMAN: David had another challenge, too – the environment around the show was shifting. Sometimes a change in leadership isn’t the only reason a business needs to be reset.

MANDEL: So Trump, yes. Whether you like him or not, everything did change.

HOFFMAN: In Veep world, Selina Meyer had gone from VP, to president, to former president. In real life, America had gotten a new president too, Donald Trump.

MANDEL: So much of Veep early on, before I ever got to it, the show created by Armando was: “This is what politicians really sound like behind closed doors, like when you don’t see them.” Well, that wall, that closed door went away. He just said what was on his mind whenever he wanted to. We did an episode in our first season where the president accidentally tweeted something, and there’s that clip of everybody going, “Oh my god, the president tweeted,” and they ran. I mean that just feels like I’m talking about a telegraph machine, that’s how ancient it feels. Like it feels like a story from pioneer days.

So, the nature of Veep changed.

HOFFMAN: David and his creative team, including the cast and crew, leaned hard in this new direction. What was once a show about the dazzling vulgarity of outwardly respectable politicians, became a story about the terrifying endgame of seeking power without consequences.

MANDEL: If Selina really wants to get the White House back, what is she prepared to do? The answer has to be: anything. The show had changed radically, but that was what the show had to be.

HOFFMAN: When the show finally ended, having won wild acclaim and multiple Emmys under both Iannucci and Mandel, there was a feeling that Veep had risen to meet the moment.

MANDEL: I think people in my position or any position where you’re coming in after someone, it’s very… What’s the word I’m looking for? Easy, I guess, to think that I should just do what the other guy did. But if you do that, you fail.

HOFFMAN: This advice is spot on – whether you’re running a beloved comedy series, or a global business. Relying on what’s been done in the past won’t cut it. You need to be able to reassess, reset, and refresh. Thank you David, for sharing this story.

OK, detour is over. Back to Satya.

Chapter 8: To refresh a culture, you’ve first got to earn it

When we left him, Satya Nadella had just become the third CEO in Microsoft’s history. Under its first founders, the company had been scaling with implicit rules and guidelines around mission. As a re-founder, Satya wanted to make these guidelines more explicit, and adapt them to a new age.

HOFFMAN: Now the other part of it, though – which is a really key thing and ties back to the growth psychology, ties back to the learning – is that you’re not just anointed as co-founder. You have to earn it to some degree. It’s not earned by getting the job. It’s earned by that first year or two of how you’re leading. What were the things that you were doing to say, “Hey, this is our mission. We are the people who could do this awesome mission. Here’s how we’re doing it now”? What were the key moves that you made that other students of hitting refresh would say, “Oh, that’s really important. I should know that now”?

NADELLA: In some sense, I always think about this as, if I was, let’s say, an outsider, I would have had to have a very different playbook. I mean, in some sense, whenever I criticize whatever it is that we may have been doing, I was not criticizing somebody else. I was criticizing myself, because I am a consummate insider. Nobody could have said, “Satya, somehow you dropped from the sky.” I mean, God, I was part of the Microsoft culture. I thrived in it.

HOFFMAN: It’s another reminder that hitting refresh on company culture doesn’t have to come from outside. It can come from a consummate insider, as long as that insider:

- is thinking holistically about the organization,

- has the humility to consider what is and isn’t working, even if they’ve been part of the problem, and

- is now in a position to effect change.

There are so many ways for this to play out. For Satya, it meant showing up with values and priorities that were explicitly defined. It was starting again, without starting over.

HOFFMAN: Let’s start at the most tactile, which is bringing a sense of empathy more into leadership. Talk a little bit about why that became an important value for you and then also, part of where your thought about, “Look, empathy doesn’t mean not making sharp business decisions. It’s actually part of being a really good and sharp leader.”

NADELLA: This notion of empathy is at the core of our learning. We are in the business of meeting unmet, unarticulated needs of customers, right? That’s the source of all innovation, all design thinking. And then you say, “Oh, how does that happen?” That happens because you have empathy for the context, the situation, that unmet, unarticulated need. You’re listening beyond the words. You’re seeing things beyond what is just playing out in front of your eyes. You learn it through your life’s experience. It’s not like I go to work and say, “Oh, I want to turn on my empathy button now, and I’m now going to be very empathetic.”

Chapter 9: Why Satya Nadella abolished stack ranking

You have to tap into the very innate human part of us. In 2014, Microsoft’s culture at that time, which was a little hard edge, quantitative, metric-driven engineering, I felt like this stuff all sounds really soft. But in retrospect, oh my God, was the organization hungry for it.

HOFFMAN: The words used to describe the refresh might have seemed soft, but the refresh itself manifested in concrete and specific ways.

HOFFMAN: One of the ones that I actually thought was a microcosm of the cultural change was getting rid of stack ranking, right? To say, “Look, not only is there what we should do, there’s also what we shouldn’t do.”

NADELLA: It became, at some point, a bad caricature of everything that was wrong in the company.

HOFFMAN: For those who’ve never had to navigate it, stack ranking is basically enforced grading on a curve. If you have a team of five people, you have to rank one as exemplary, one as good, one as average, one as below average, and one – let’s call him Kevin – as poor. Even if all five, including Kevin, turned in exemplary work last quarter.

The reason behind this system is, to oversimplify a little, motivation. If you know there’s a top spot, you want each team member fired up to get it. What can happen in practice, however, is that Kevin treats his very own teammates as competition. If he can beat them, he wins, and they lose.

Regardless of the initial reasons behind it, stack-ranking had become a notorious culture-killer at Microsoft, and it was reviled within the company. So, Satya got rid of it.

NADELLA: The principal issue of any system like stack rank has, is it doesn’t leave room for judgment, which is, who said that a team cannot have all above-average performers?

We all know that performance is, in some sense, relative. The world measures us that way. But at the same time, you can have periods of people performing in one team extraordinarily well, and they should be rewarded for it. In fact, the stack rank, I think, artificially took away the power of an individual manager in being able to distribute rewards.

HOFFMAN: Some of you may be thinking, “Fine, but if I’m not a leader, what can I do to change something like stack-ranking? It’s totally out of my hands.” Well, that’s not the whole story.

Remember Satya’s experience at the meeting where he wanted to speak up, and didn’t? This is again a place where speaking up is its own small, strategic refresh button. You don’t have to put your career, or your relationship with your boss, at risk to make this happen. Even in the most rigidly structured companies, there are usually some avenues to give feedback, such as project post-mortems or 360 reviews.

That doesn’t mean you’ll see instant change every time you raise your hand. But if you have the means to speak out and speak up, DO. Employee disgruntlement around stack ranking was what let Satya know he should kill it. Their feedback was a crucial step in the refresh.

Chapter 10: Microsoft takes a fresh approach to acquisitions — including LinkedIn

Another way Satya helped reset Microsoft was in his approach to acquiring new companies, including LinkedIn.

HOFFMAN: Another thing that I’ve seen in your leadership – and personally seen from my own experience – is a very intelligent approach to M&A and acquisitions. There’s obviously the LinkedIn side, which started with some very early conversations of just “get to know you” and saying, “Hey, let’s establish a relationship.” I think this is part of your partnership background. It’s like, “Look, let’s just talk and help each other and then see where the conversation goes.”

But it isn’t just LinkedIn, of course. There’s everything from Minecraft to GitHub and all of the others. Okay, let’s take a first principles rethink and a cultural evolution. How has that shaped your approaches to M&A in terms of what kinds of companies but also how to do it, how to evaluate it, how to make it successful?

NADELLA: Yeah, I mean, in a fairly major way, I distinctly obviously remember my first set of conversations with you. I mean, you were clear. I remember first broaching the subject, and you were clear, “Hey, look, we are enjoying building LinkedIn. We have no interest in any conversation about acquisition.” But as you said, you mostly wanted to start to talk about, “Hey, what do you care about? What are you doing at Microsoft? Here’s what we’re doing at LinkedIn. Is there really stuff for us to talk about that is meaningful to our members?” So, I’ve looked at M&A as at the meta level, it needs to do two things.

One is it needs to be something that we can clearly say, “It fits our mission. It fits our identity,” or “We can be a better owner,” which is a very narrow way to talk about it. But can we say, “Oh, as part of Microsoft, will a LinkedIn, a GitHub, a Minecraft fit, thrive, and flourish?” Then the second aspect, which is also equally important to me is, “How will Microsoft change because of a LinkedIn, a Minecraft, and a GitHub?”

HOFFMAN: This more symbiotic approach to M&A contrasts sharply with what the Microsoft of old might have done.

NADELLA: There’s no such thing as a static company that can somehow survive the changing circumstances. So, to me, that’s what it represented. One theme that was clear is, “What was Microsoft weak at?” We didn’t get networks. We didn’t get communities. We did not understand what virality meant at scale. Also, the business model implications of it. We were weak in all that it meant. So, therefore, it is very important for us. Even though Minecraft, yes, was a game, I saw it as a metaverse. I didn’t see it, “Oh, here is just another game.”

HOFFMAN: This is exactly the type of perspective that re-founders bring. A first founder can get a company to a powerful place in society. The re-founder has to – and gets to – ask, how do we earn keeping it?

Chapter 11: How do we earn the right to play a big role in society?

HOFFMAN: This is a good place to ask you to highlight something I’ve heard you say a lot internally, which I think is a very good part of leadership and as a reflection of part of what growth psychology and growth mindset really means, which is: How do we earn the right to be the provider here? How do we earn the right to play this role in society?

NADELLA: When I think about the license to operate for a company, where does that come from? I am very deeply influenced by this statement by Colin Mayer in his book called Prosperity, which I think is a good description of, “What is the social contract of a corporation?”, which is to find profitable solutions to the challenges of people and planet. The two keywords being that profitable solutions, but the other one being the challenges of people and planet.

So, whenever I think about Microsoft, I feel like, hey, we get to operate as a multinational company in all the countries we operate in by ensuring that there is real symmetry between us doing well and the world around us doing well.

HOFFMAN: I couldn’t agree more. Pursuing symmetry between the health of your business and the health of the world around you is how you earn the right to be a provider at scale. It’s a measure of how well you are living your values as a company. That doesn’t mean you’re bad if you happen to be succeeding in an economic downturn. But your definition of success should include the success of the community around you.

And by the way, the CEO isn’t the only one who determines this. Any employee can and should regularly ask, “Do our daily operations make the world around us better? Are we acting in a way that serves the mission?” Making a regular practice of asking that question is acting like a re-founder.

Part of Satya’s re-founder mission has been to prioritize collaboration over exclusivity, in moves that might have shocked the Microsoft of the late 1990s – like partnering to build AI applications with a nonprofit company.

HOFFMAN: One of the things that I think is something you would do that neither Bill nor Steve would have done is the partnership with OpenAI and the focus on that being the play. Obviously, we both have 100 out of 10 respect for both Bill and Steve. So, this is not a criticism of them. It’s simply a different way of playing the game. Say a little bit about how you thought about, “This is why it’s important for Microsoft. This is why it’s important for the right outcomes in the world. Here are the kinds of things we’re doing by partnering with an external technological organization that is actually in fact a 501(c)(3) about how we’re navigating these joint missions together.”

NADELLA: One of the things that influenced me a little bit was I’ve never heard this directly from Bill, but when he set up Microsoft Research, one of the social contracts of Microsoft Research was, after all, Microsoft wouldn’t have existed if it was not for the broad contributions of the research community at large, which led to the internet and led to all of the technologies that made it possible for Microsoft to exist.

So, you always had as a percentage of some R&D, we’ve got to do fundamental research with in some sense, no strings attached so that we can contribute back. So, that has always stuck with me. If AI is going to be one of the most defining technologies, what is an organization that is going to do work? And then how are we then going to be able to partner with that organization to even further democratize it?

I think of it as a continuation of, “How do we stand for being that platform company, that developer tools company, with a broad mission to democratize the most defining technologies?” In fact, I say, if it was, oh, wow, the two companies in the world or three companies in the world have AI, that’s not a world that any of us want to live in. In fact, that’s a world that won’t exist. No country will allow that. It is a silly way to even conceptualize it. So, therefore, this thing about sometimes when people say, “Oh, you know what? We are the AI company,” I say bullshit to that, because the world doesn’t need you to have AI. The world needs AI.

HOFFMAN: Yes, we are bringing AI to the world, but not only us and only us.

NADELLA: Exactly.

HOFFMAN: Incredibly, a company that was once hauled before Congress to defend a monopoly on how people get online is now partnering with OpenAI, and working towards global access. And this shift away from a need to dominate has, actually, made Microsoft more successful than ever.

NADELLA: Going back to your fundamental thesis, at some point if you’re successful, you will outlast your founders as a company. If you are going to outlast that founder, that handoff is going to be super critical.

HOFFMAN: Successful businesses are meant to outlast their founders, which is why re-founders need to be part of the design. So wherever you can, look for those re-founders, and take on that founder mindset, wherever in the company you are.

I’m Reid Hoffman. Thanks for listening.