How to unlock your team’s creative potential

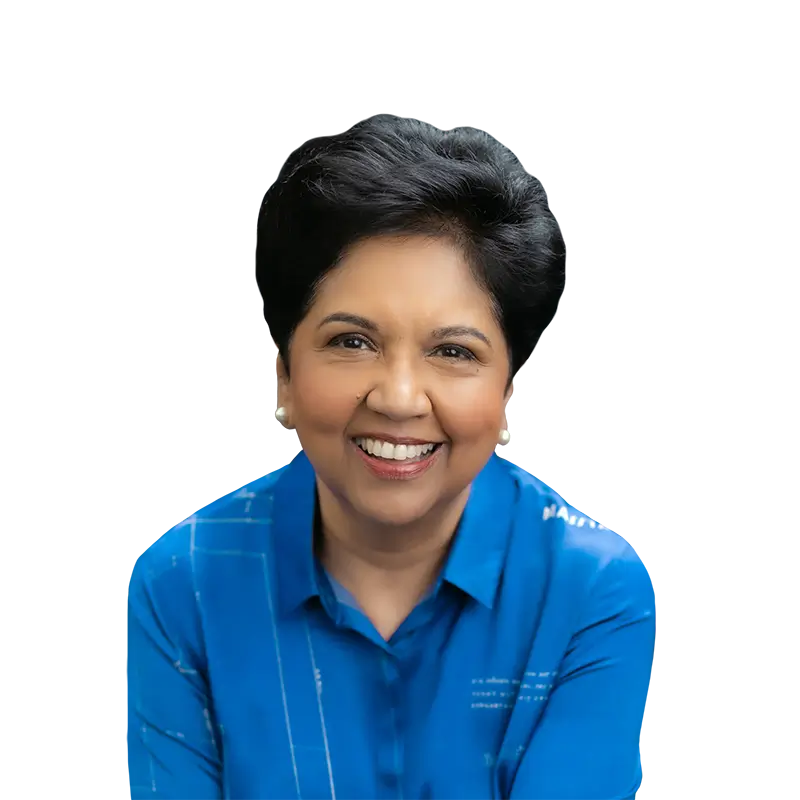

To get the most out of your talent, you need to create an environment that allows them to thrive. Nobody knows this better than Indra Nooyi, who spent 12 years as the CEO of PepsiCo. Her drive to support talent underpinned the initiatives that transformed the company. “I looked at each person in my company, not as a tool of the trade,” she says, “but I looked at them as an individual asset that had to bring their head, heart, and hands to the company for us to be successful.”

To get the most out of your talent, you need to create an environment that allows them to thrive. Nobody knows this better than Indra Nooyi, who spent 12 years as the CEO of PepsiCo. Her drive to support talent underpinned the initiatives that transformed the company. “I looked at each person in my company, not as a tool of the trade,” she says, “but I looked at them as an individual asset that had to bring their head, heart, and hands to the company for us to be successful.”

Transcript:

How to unlock your team’s creative potential

INDRA NOOYI: So just imagine this big room with shiny red floors and not much furniture; there’s probably one chair in that entire room. But right in the middle hangs this rosewood swing, and it’s hanging on chains that were built into the wall.

HOFFMAN: That’s Indra Nooyi, former CEO of PepsiCo. And that rosewood swing she’s describing was the centerpiece of her childhood home in Madras – now Chennai – in India.

NOOYI: And it’s in use all the time because the various women in the house in particular would come and sit on the swing, and they’ll be chatting away on politics and family and gossip and children’s grades.

And then when the elders got together, it was all about let’s match all the horoscopes, for the various girls and boys that need to be matched.

And when they were not there the kids jumped on the swing, and boy, did we have a rocking time. It just went as high as it could.

All the cousins would sort of pile onto the swing, and we’d sing. We all had the same repertoire of songs: the Beatles and Beach Boys and Cliff Richard. So for about two hours, we could sing all these songs. It was one hell of a musical fest. And you could time the musical swing so that the creaking gave you a beat for the music, and you just went on and on and on.

So it was the centerpiece of the living room, and it hangs there even today. My kids just love it.

HOFFMAN: Every founder, entrepreneur and leader must make your version of that rosewood swing by creating an environment that’s stimulating AND sustaining for each and every person in your company. Just like for all of Indra’s family members, that seat is the focal point of family life, and the basis for interacting, growing, and thriving.

So build your swing, and keep it swinging. Get it right, and you’ll be releasing the full creative potential of every member of your team. Get it wrong and you’ll stifle their talent and your company’s chances of success.

That’s why I believe you need to create an environment that lets talent thrive. Let people push their own creative boundaries, and they’ll do the same for your business … and for you.

HOFFMAN: I’m Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn, partner at Greylock, and your host. And I believe you need to create an environment that lets talent thrive. Let people push their own creative boundaries, and they’ll do the same for your business … and for you.

As a kid, did you ever poke around the pools of a rocky shoreline in search of fish, crabs, or other aquatic wonders?

Perhaps you collected some in a bucket for closer inspection. You may even have been tempted to take some home with you.

But unless you have a proper aquarium, it’s unlikely that all of your fishy friends would have done well in their new environment.

For your marine menagerie to thrive, you’ll need to know what each creature needs, how they can best support each other, and how you can create an environment that will stimulate all of them.

Gathering and sustaining talent for your company poses a similar challenge. You need to be proactive about finding talent. But you can’t then just transplant that talent to your own environment and expect it to thrive.

Before we go on, it’s worth defining what it means to thrive in your work.

A big part of that is letting people bring their full selves to what they do.

A founder by default brings their entire self to work. There’s no other way to do it. As the leader of a startup you need that 100% commitment to your mission and your product.

But when it comes to the people you want to bring along with you, you need to look at far more than their skills and how they can help your company.

I wanted to talk to Indra Nooyi about this because she spent a huge part of her time as CEO of PepsiCo thinking about how to encourage talent at the company to thrive at all levels. During her 12 years as CEO, she grew multi-billion-dollar revenues by more than 80 percent. And since stepping down from that role in 2018, she has continued to think about this problem on a societal scale.

It’s a problem she’s experienced first-hand.

NOOYI: I want you to put yourself in India in the seventies. A couple of decades before, they’d gotten independence from colonial rule. And India was still a poor country, slowly finding its footing.

But I had won, in many ways, the lottery of life, because I had a stable family. We had a roof over our head that was permanent. We had a home, so that’s another lottery of life. I went to the right schools and colleges. I was born with a brain.

So I had lots of things that worked in my favor. Now with all of these benefits, I actually went and got a master’s degree in India. At a time when very few women went to professional schools, I was in one of the business schools. And the biggest lottery in my life was that the men in my family and my mother thought that men and women should both be educated and should do whatever they want. So I had the luck of the draw.

HOFFMAN: After graduating business school, Indra joined the India office of Johnson & Johnson as a product manager. For her first assignment, she was charged with bringing a new line of sanitary pads to the Indian market. The task involved working around deep cultural taboos and sensitive customer research. It was just the kind of situation that could end up stifling innovation. But Indra took the challenge head-on.

NOOYI: In families like ours and most families, nobody spent money on packaged personal protection. It was always homemade, personal protection, very uncomfortable, very restrictive.

The U.S. sent us a product, but we had to now retool the product for the humidity conditions in India, because adhesives behave differently under different humidity conditions. We have to decide the optimal one offering and how does it fit the Indian human ergonomics? So I had to request women to leave their used pads, so I could inspect what the shape of the pad was after use.

India did not allow advertising for sanitary napkins those days. So we had door-to-door conversations with mothers. We’d go to schools and colleges and educate women on the freedom of using this sort of sanitary protection. It was a whole different approach to marketing.

HOFFMAN: Indra’s ingenuity and perseverance were central to making the new product a success. And fortunately, she was given the space to come up with novel solutions to overcoming the cultural taboos.

NOOYI: Now, what was amazing about J&J is most of the bosses were men, but you go to them and talk about how the form function had to change, or whatever. They listened carefully, and they acted. So there wasn’t a question of making you feel embarrassed talking about this. So once we had the product and everything designed, now the challenge is distribution and advertising.

HOFFMAN: Indra’s bosses at Johnson & Johnson trusted Indra with a new product launch. Yes, they saw her talent; but more importantly they saw her creativity. And that creativity provided solutions to the obstacles they faced. They saw that helping her thrive gave their product the best chance for success.

Indra was set for a strong career at Johnson and Johnson. But within a year of joining, she felt the need for a new challenge.

NOOYI: In those days there was only one country that was the seat of innovation, the seat of creativity, the seat of excitement, the best music, the best fashion, the best culture. We devoured everything American.

And for young people graduating from college, there was only one place to grow, and thrive, and bring out your full potential. And that was the United States. All of the best brains in India were leaving India for the United States because they said, if I can learn from the U.S., if I can contribute to the U.S., I’m going to be a better person. It was an aspirational move.

HOFFMAN: Indra graduated from the Yale School of Management and then landed a job as a strategy consultant at Boston Consulting Group. The role involved parachuting into different businesses, quickly getting up to speed and helping them overcome specific problems.

NOOYI: I loved consulting. I loved the way we approach problems. I loved the way you think about frameworks to address issues, and how you bring the experience of multiple industries to solve the problem of one industry.

HOFFMAN: Consulting gave Indra the challenge she needed to thrive. After six and a half years at BCG, Indra was recruited by Motorola, then moved to manufacturing equipment maker ABB.

Some years into her career in the U.S., Indra found herself fielding offers from GE and PepsiCo.

NOOYI: I was more of a technology person than I was a consumer goods person. So naturally I was leaning towards GE because the potential was huge. PepsiCo was a fantastic company, but my technology bent was taking me more towards GE.

HOFFMAN: However, an impassioned pitch by PepsiCo’s CEO at the eleventh hour swayed her.

NOOYI: I’d promised both companies I was going to make a decision on X date. And about three days before that decision date, I get a call from Wayne Calloway.

HOFFMAN: Wayne Calloway was the CEO of PepsiCo at the time. And his pitch to Indra is worth taking some time to examine.

NOOYI: He proceeds to talk for about 10 minutes explaining to me why GE is a fantastic company. Jack Welch is a legendary CEO. “I was on the GE board meeting today, and Jack said you’re going to join GE. I understand why you would want to join GE. It’s a great company. But you said you were going to make up your mind in three days. I’m going to take you on your word. Let me tell you why PepsiCo needs you.”

And he made the case for why PepsiCo needs me. Somebody like me had never been in the executive floor. They wanted somebody to give them a different frame of thinking, how they were going to support me, mentor me, develop me. And he made a plea for me to join PepsiCo.

HOFFMAN: What might surprise you about this story is that Wayne also happened to be a board member of GE – the very company that was also vying for Indra. And so something struck Indra about the pitch.

NOOYI: So at no point in time, did he say I’m better than GE. In fact, at every point he played up GE. That’s the kind of a human being that he is.

HOFFMAN: Wayne Calloway’s attitude was the hook. But it was something else that he said that reeled Indra in.

NOOYI: What Wayne was basically saying is: your 360-degree view of industry, and what you’d bring to PepsiCo, and what we are willing to hear from you and act on is something that’ll make you feel very, very good about your time in our company. Count on me to use that wisely and to put it to good use at PepsiCo.

HOFFMAN: “Count on me” – this is what you want to be saying to your team explicitly and implicitly when it comes to helping them thrive. Count on me to understand your passions. Count on me to make sure that you have the freedom to innovate. And count on me to ensure that you grow as part of the team I’m leading.

Wayne wasn’t just relying on Pepsi’s existing reputation. Rather, he was laying out how Pepsi needed to change. And how was it going to change? Indra.

Wayne’s pitch was aspirational for both Indra and Pepsi. Here’s how Indra responded.

NOOYI: Holy cow, I’m going to join this company if this guy is the leader. So that day, I walked out of the ABB office into PepsiCo and said, “I accept.”

HOFFMAN: Indra joined PepsiCo as Senior VP of Strategic Planning. She was immediately tasked with a daunting prospect: evaluate what was wrong with PepsiCo’s underperforming restaurant business – which covered Taco Bell, Pizza Hut, and KFC – and then propose how to solve it. Indra and her team worked around the clock, visiting restaurants and diving into the figures. One of the problems they found was that there were simply too many restaurants cannibalizing each other’s business. But there was another, deeper issue.

NOOYI: PepsiCo is a packaged goods company. Restaurant is a service industry. And for a service industry you need experienced people who love the restaurant business, running restaurants. We would take hotshot packaged goods people, push them into restaurants, and all of a sudden they’re looking for a packaged goods solution to service business.

HOFFMAN: PepsiCo was taking talent that thrived in a packaged goods company, and transplanting it into the alien landscape of restaurants. At the same time, it was stifling the talent that would normally thrive in the restaurant business.

NOOYI: We were putting a lot of bureaucracy on restaurants – that was okay when you were stamping out billions of bags of snacks or beverages. But I still remember the scene when I went, in the morning, to a restaurant as they were opening. Over the night, they print out a hundred reports automatically.

In the morning, the restaurant guy would come into the store, take the reports, and put them all in the garbage. And he had his own book where he kept his records.

HOFFMAN: This scene was being repeated every day in thousands of restaurants. In most cases, the managers and staff knew what needed to be done to make their restaurant thrive. But they weren’t being given the space or trust they needed. And this meant their motivation and drive to innovate was being crushed a little more each day. This had been happening for years, and no one in the head office had noticed. Until now.

Indra knew something needed to be done quickly.

NOOYI: We had to reinvent how PepsiCo should play in the restaurant business and come to terms as to whether we should be in that business at all.

Ultimately after two years, we decided to unfetter it.

Because it was a completely different culture, different business model, and the best way for it to be successful was to be separate from PepsiCo.

HOFFMAN: It was a radical and controversial plan, but Indra convinced her CEO and the board it needed to be done. By then, she knew the company had given her room to think big and take calculated risks. So in 1997, PepsiCo spun out their entire restaurant business under a new brand, Yum. It has gone on to be one of the world’s most successful restaurant businesses.

With this victory behind her, Indra set her sights on making the rest of PepsiCo a company where innovation could thrive.

Her next task was fixing the company’s international beverage business. Indra headed up the 3.3 billion dollar acquisition of Tropicana, and then a merger with Quaker Oats. In 2000 she became the CFO. A year later, she became president. Then, in 2006, she took over as CEO.

NOOYI: When I took over as CEO of PepsiCo, I realized that I was being given an incredible opportunity to shape an iconic company, to be even more successful into the future. And I also knew as a CEO, my job was to manage the company for the duration of the company, not the duration of the CEO.

HOFFMAN: In business terms, this meant focusing on healthier products and reducing the company’s environmental impact.

But it also meant making PepsiCo a place where talent could thrive. And it’s THIS drive to support talent that underpinned all of Indra’s initiatives to transform the company.

We’re back with Indra Nooyi, former CEO of PepsiCo. If you’re enjoying this episode and want to share it with friends, send them the link mastersofscale.com/nooyi. That’s N-O-O-Y-I. And to hear my complete interview with Indra Nooyi, become a Masters of Scale member at mastersofscale.com/membership.

Before the break, Indra had just become PepsiCo’s CEO, and she was already setting in motion her bold plans for the company.

NOOYI: For big iconic companies to remain successful, we needed the best and the brightest. So we needed the best and brightest talent, irrespective of gender, ethnicity, orientation, don’t care.

HOFFMAN: Building an environment in which talent can thrive goes hand-in-hand with long term thinking. Indra knew this, and she also knew she had to be proactive in reinvigorating PepsiCo.

NOOYI: I look at our own products and say, “God, we have evolved over time to become a cacophony of colors, but we really haven’t made our products invite consumers into the product. We haven’t created this strong, passionate bond between us and the consumer.” And I’m not sure we even thought about the user experience in terms of the product size, the bag, how it sits in the pantry. The classic example was SunChips.

HOFFMAN: In case you haven’t tried them, SunChips are crinkly, bubbled multigrain chips. They were a staple in the PepsiCo snack pantheon. But for Indra, something about them seemed stale. She went to her design department.

NOOYI: I said, “This is a great product. Who is it targeted towards?” They said, “Mostly women like this whole grain, SunChips, the taste of it.” I said, “Really? But then why is each SunChip an inch and a half by one inch and a half? How is somebody going to bite it and what do you think a woman’s going to bite it? It is going to crumble all over. Why can’t you make it a little bit smaller and make it more friendly to women who would like to consume the product on the go, because that’s what we want? The answer was, “Well, the way our molds are cut in the manufacturing process, this is the size that can come out of it.”

HOFFMAN: This is a classic example of how innovation can be stifled by the way you structure your business. The people in the design department weren’t lazy or incompetent. But their instinct to yield to the manufacturing process put a subconscious lid on their creativity.

Your role as leader is to blow off any lids like this – and make your company a place where innovation is supported rather than restrained. And this is exactly what Indra did.

NOOYI: I go, “I don’t care. We’re going to make a smaller SunChip.” You don’t start with what manufacturing can do. You start with: What does the consumer want?

HOFFMAN: Indra made this sentiment the heart of her proposition to new talent. Just as Wayne Calloway had told her to count on him to make PepsiCo a place where she could thrive, Indra would be saying the same to every new hire: “Count on me.”

NOOYI: When you come into PepsiCo, you can bring your whole self with you. We’re going to create an environment where you can be a mother, or father, or sister, or brother or a citizen of the community, and be an employee of PepsiCo. Because we’ll help you find a way to balance it all.

HOFFMAN: This was central to Indra’s signature drive to reform the company. She called it “Performance with Purpose.”

NOOYI: Let’s keep delivering great financial performance, but let’s do that with a view to changing the portfolio, being more environmentally conscious and creating a wonderful environment for our people. And if we did that, we’d future-proof the company, and that will continue to deliver great results into the future.

So the combination made for strong backbones and performance and purpose together self-reinforced each other and it actually galvanized our employees. It brought out the passion in them. They would now walk tall with their families and their friends and say, “I’m working for a company that’s singularly focused on three planks of purpose that really are good for society, is good for communities, and make employees walk tall.”

HOFFMAN: Indra set about seeding the talent base with some key hires.

NOOYI: I hired myself, perhaps, the best head of R&D. I think that’s the best hire I made. Because Mehmood Khan walked into PepsiCo, he was head of R&D at Takeda. He said, “Why would I leave Takeda and this huge R&D budget, to come and work for PepsiCo in consumer products, with such a tiny budget?” I said, “Mehmood, the big difference is in PepsiCo, you can make change on a large-scale basis, and you can taste every product you make,” which you cannot in pharmaceuticals.

HOFFMAN: Mehmood was sold on the pitch.

NOOYI: It was transformative because Mehmood brought a scientific sensibility to PepsiCo, and he was a talent magnet. Everybody who knew Mehmood wanted to work at PepsiCo. And all of a sudden, we had taste experts or mix experts, metabolomics, genomics experts who wanted to come to PepsiCo. And we built, I think, the best R&D team in the food and beverage industry. They reduced salt content, sugar content, reduced water usage, fundamentally changed many dynamics of our supply chain and really made a difference to the innovation pipeline at PepsiCo.

HOFFMAN: Perhaps more importantly, Mehmood set up a system to unlock innovation across the company.

NOOYI: What Mehmood did was create flavor banks so that all flavors around the world were all in one bank, as we call it. So anybody in the world could look at this flavor bank and say, “How can I take this and adapt it for me?” As opposed to, “How do I start from scratch, creating a flavor?” Failure rates were much lower because we made sure that the product would work because of other people’s experience.

And we also laid out in the data bank what doesn’t work. It unleashed productivity. It started to create a good internal competition. Why is it this line in Russia is more efficient than this line in the UK or this line in Mexico? Each one wanted to learn from the other. All of a sudden the power of this global enterprise is now coming into play.

HOFFMAN: It wasn’t just the R&D environment. Indra looked for opportunities across the whole company to encourage talent to thrive. Here’s another example, this time from the design department.

NOOYI: It occurred to me that we needed to bring a new kind of thinking into the entire experience of how our product is conceived of to how is it designed? What are the pain points in the interaction? What are the joyful moments of interaction?

HOFFMAN: To kickstart this new kind of thinking, Indra hired Mauro Porcini, head of design at 3M.

NOOYI: He transformed user experiences, transformed every part of PepsiCo’s touch point with the consumer. And all of a sudden, consumers loved us, customers loved us, our retail partners, our food service partners loved us, and everybody wanted to partner with us.

And pretty soon, we were in the Milan Design Week showing PepsiCo. We were a hot ticket for young designers who wanted to come and work in consumer products. The most iconic designers wanted to work with us.

HOFFMAN: Key hires like Mehmood and Mauro made PepsiCo into a place where driven, creative people wanted to work. The hires were clear signals that PepsiCo valued talent and that it was willing to mold itself to them, so they could go on and help mold the company’s future.

Indra didn’t just focus on new hires. She came up with ways to help existing employees thrive. One of these ideas was sparked when she visited her mother in India, and saw the reaction her mother’s friends had to hearing that Indra was now CEO.

NOOYI: They’d walk up to my mother and say, “You should be so proud. You brought up this kid. It’s because of you that she is who she is, and congratulations and kudos to you.” I sat back and thought about this and said, “Wait a minute, I have never thanked the parents of my executives who gave me these extraordinary leaders that’s made the company successful, that’s making me successful.”

HOFFMAN: So Indra decided to do just that.

NOOYI: “I’m going to write to the parents, and as many, as possible, of my direct reports, I’m going to visit their parents and in person thank them, but for sure, they’re going to get the letter.”

Parents loved it. In fact, many parents framed it and put it in their homes. So it led to a wonderful relationship between their parents and me. I wrote letters to I think the parents of about 400 executives and met maybe 20 executives’ parents in person, but we had a wonderful relationship. So if the executive went home and said anything negative about me, it was, “Uh-huh, she’s my friend. Don’t even bother.” So it created a beautiful relationship between me and the families of my executives.

HOFFMAN: Giving talent a place to thrive isn’t just about providing a challenging, fulfilling environment; it’s about recognizing people. You don’t have to go so far as writing to their parents, but you do need to do things that take account of them as human beings. And those things should be authentic to you.

NOOYI: I looked at each person in my company, not as a tool of the trade, but I looked at them as an individual asset that had to bring their head, heart, and hands to the company for the company to be successful. And if you were not treated for who you were, if I didn’t bring out the best in you, the company lost out.

HOFFMAN: For another perspective on the importance of diversity and individuality, we spoke to Nicole Burke, founder of gardening skills platform Gardenary. It turns out a garden also needs a multitude of individuals to thrive.

NICOLE BURKE: A huge mistake most of us make in the garden is planting a ton of one thing. That’s actually a huge challenge that exists in our farming culture in the U.S. right now. It’s called monocropping. As you can imagine, basically any kind of disease that starts to touch one of those plants or any kind of pest, those things are just going to have a heyday.

HOFFMAN: It’s why Nicole’s garden may, at first glance, seem like an unruly mix of plants. But there’s a method to the madness.

BURKE: So if you look at any of my gardens, it looks like a crazy world in there. It’s wild.

It’s this magical combination. It helps protect against pests, it helps protect against disease. There’s no room for weeds. They’re all bringing different kinds of nutrients into the soil as they grow, and they benefit each other.

HOFFMAN: This is what Indra set out to achieve at PepsiCo, making it a vibrant garden of talent in which ideas would cross-pollinate. As well as increasing the daring and diversity of her hires, Indra wanted to cultivate a company-wide culture in which innovation was prized.

And when you listen to what Indra’s about to say, keep in mind the stereotypes that divide young startups and multinational megacorps.

NOOYI: I would argue innovation is probably the toughest science, discipline, art, whatever you want to call it, to make happen. If you’re a big company, don’t forget PepsiCo was $63, $65 billion. If we wanted to keep growing revenues at 4% to 5%, we had to grow net revenue at $3 billion every year, which means gross revenue of about $5 billion, because there’s some cannibalization. Imagine growing net revenue at $3 billion at 49, 59, 99 cents at a time, because that’s what a bag costs. So the innovation hurdle is huge, it’s huge. So whether you’re a small company or a big company, how you think about innovation, how you groove the whole company to think creatively is a big challenge.

HOFFMAN: This gets to the heart of why those stereotypes about startup vs established company are so wrong. It’s easy to assume that innovation is second nature to the small, scrappy startup. And it is. But it’s easy to forget that innovation is not like the first-stage booster of a space rocket that you jettison once you’ve reached a certain height. It’s just as essential at every stage of your business. And this is why intrapreneurs are just as essential to large established companies as entrepreneurs are to startups.

NOOYI: Innovation is tough under any, any circumstances. You’ve got to build the muscle for it. You’ve got to build the capability, the mindset, the tools, if you want to have a low cost of failure, that’s what you have to do.

So the question is, how do you lift and shift ideas to truly leverage the scale of PepsiCo? Now that requires a mindset that says the company is a borderless company. It’s a non-siloed company. That was one of the biggest challenges I faced as a CEO, because people like to own everything. People like to say, “This is my idea. I want to get credit for it.” To me, you should get credit because you control and collaborate, not because you just control.

HOFFMAN: Since stepping down as CEO of PepsiCo in 2018, Indra has worked to help talent thrive in the wider world, and she’s made it the center of her book, My Life in Full: Work, Family and Our Future.

NOOYI: Even though the book sounds like a memoir, it didn’t start off as a memoir. It started with me writing some articles about the whole issue of: How do we get all of the people who are talented in our economy to serve the economy? Because that’s what we need. We need all the talent.

Lots of women graduate with top grades. They are 60% of the professional degrees, but they’re not rising in their careers. The issue is not the women, the issue is that we don’t have the support systems to enable them to have families and be in the workplace.

And as a country, we don’t have enough support systems, either from families, or from the government, or from our communities to enable them to balance the two. So families become a source of stress rather than a strength.

I think it’s a loss for the country. I’m not talking as a feminist, I’m talking as an economist. And so, we have to fundamentally tell ourselves, if we want the entire talented population to be in the service of the country, we better look at them as a system and their holistic life. If you look at them as real assets, you’ll worry about them, their families, how are they going to balance all of this? You’ll come to very different solutions.

HOFFMAN: I couldn’t agree more with Indra.

I couldn’t agree more with Indra. There is a huge pool of under-represented and overlooked talent in society. And by failing to engage it, we’re not just failing ethically, we’re also failing economically. Which is why we should be taking every opportunity to create companies and communities that allow every talent to shine.

I’m Reid Hoffman. Thank you for listening.