How to unite a team around a shared mission: A story from Spark & Fire

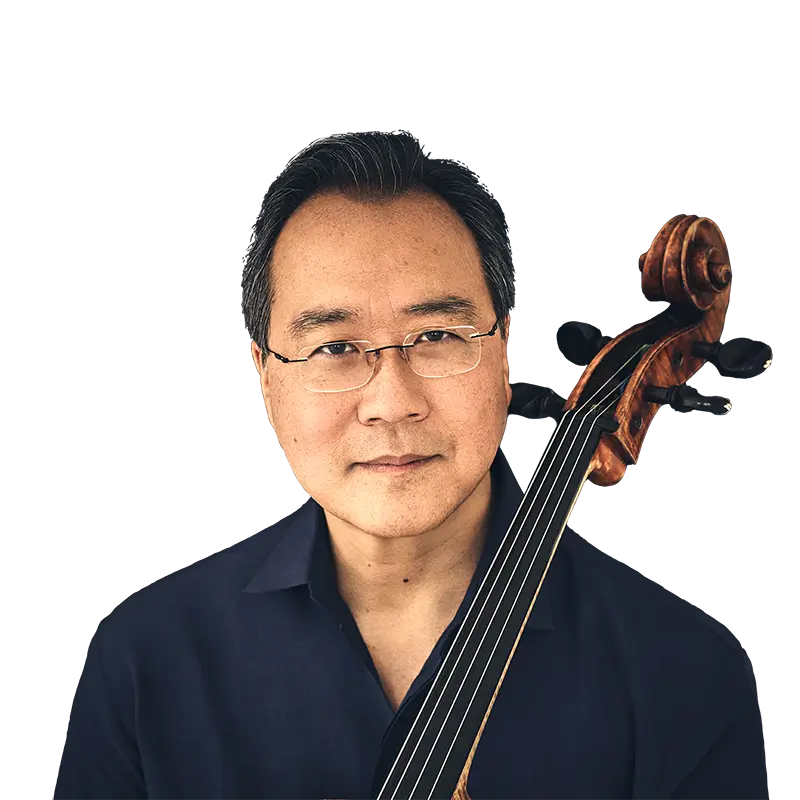

What can an entrepreneur learn from a world-class musician? How to create a world-class team, and unite around a clear mission. In this special crossover episode with our sister podcast, Spark & Fire, you’ll hear world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma tell the story of co-founding The Silk Road Project — a musical collective that brings together musicians from wildly different traditions to write and perform original music.

What can an entrepreneur learn from a world-class musician? How to create a world-class team, and unite around a clear mission. In this special crossover episode with our sister podcast, Spark & Fire, you’ll hear world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma tell the story of co-founding The Silk Road Project — a musical collective that brings together musicians from wildly different traditions to write and perform original music.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

How to unite a team around a shared mission: A story from Spark & Fire

REID HOFFMAN: Hi listeners. It’s Reid. You may have noticed we’re in your feed a day early. That’s because what you’re about to hear is a special crossover episode with our sister podcast, Spark & Fire. And it features cello virtuoso Yo-Yo Ma.

Spark & Fire brings you stories of creative journeys, from first-class artists and innovators at the top of their game. These are stories of building from the ground up — with all the entrepreneurial thinking you hear on this show, applied to creative fields. And it’s hosted by our own executive producer, June Cohen.

Season 2 has just launched.

So what you’ll hear now is one part of a Spark and Fire episode that we think will resonate with our community of entrepreneurs and business leaders. But you can listen to Yo-Yo’s full episode right now. Find the link in our show notes, or at sparkandfire.com. Make sure to subscribe, so you never miss a show.

We’ll be back to our regular schedule next Tuesday, with a new classic episode of Masters of Scale.

YO-YO MA: You go to a public beach, it’s filled with people. You go a hundred yards away, it’s fewer people. You go 500 yards, it’s absolutely almost nobody. Now, any one of those people that are at the entrance of the beach can go to the place that’s 500 yards away, but they don’t. And that’s the tension that we all have as human beings. We want to congregate together. We want to be part of a group, but we also want something special. By making that extra effort and walking those 500 yards, you get to something special, but not everybody wants to do that.

HOFFMAN: That’s world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma. And across his career, he’s built a reputation for always going that extra 500 yards. He’s recorded more than 90 albums and won 18 Grammys. And he’s played for audiences all over the globe.

But the story you’re about to hear isn’t about what Yo-Yo accomplished on his own. This is about Yo-Yo co-founding the musical collective The Silk Road Project, named for the ancient trade route that ran from China to the Mediterranean. Silkroad brings together musicians from wildly different traditions to write and perform original music. Performers don’t always speak the same language — musically or literally — but in this ensemble, they manage to come together and create something totally original.

There’s a lot entrepreneurs and business leaders can learn from the Silkroad story, which was originally captured on our sister podcast, Spark & Fire.

Right now, what you’ll hear is a taste of that episode — how Yo-Yo recruited the right people, leveraging his network to form a team. And you’ll see how that team had to improvise and pivot while building the Silk Road MVP. These are all essential lessons of entrepreneurship. And I’ll come back in key moments to talk about them, throughout the show.

Now, here’s June Cohen, to welcome you to Spark & Fire.

[SPARK & FIRE THEME MUSIC]

Why Yo-Yo Ma started the Silk Road Project

JUNE COHEN: How do you build a creative vision? Look for signs that the world is changing, and then look for the scouts who can help you lead the way.

MA: In 1996, someone says to me, “You got to think of something to do for the Hong Kong changeover. It’s British colonial rule. It’s 150 years of humiliation, so we’re going to kick the British out, and this is the return of Hong Kong, it’s going to be … “

And I thought, “I can’t participate in that because, obviously, Britain and China are more than that moment of history.” Because I loved archeology, I knew that there was a set of huge bronze bells that were discovered in 1978. There was something in the technology of the alloy that when you play it, it actually has two tones, which nobody’s been able to replicate since that time.

I thought, you know, they’re 2,500-year-old bells. If we could play this piece with the bells, with a children’s chorus from Hong Kong, then you have 2,500 years of history, and you have the future. All of this fueled the Silk Road because it gave experience of saying, “okay, well, we know about these traditions and that traditions, and what else don’t we know?”

In 1998, we formed the Silk Road Project. We raised money so that we could find the scouts that would go to Central Asia, that would go to Mongolia, that would go to China, that actually know the territory, can gain the trust of the local people. They went for years, scouted and found composers, and then we commissioned them to write pieces, find the musicians, and bring them over.

HOFFMAN: What jumps out to me from Yo-Yo’s story is how the moment he got the idea for the Silk Road Project, he started thinking about how to recruit others to his mission. He would need scouts, who would be trusted by local communities. He’d need to fundraise to support this multi-year project. And he’d need all of these stakeholders to recruit from their networks, communicating that same passion for the mission.

In fact, let’s hear some of that passion from a few Silkroad members, in their own words. We’ll start with founding member, Wu Man. She’s a pipa player, one of the best in the world. (And if you don’t know what a pipa is, that’s a great reason to check out the full episode of Spark & Fire in their show feed!) Here’s Wu Man, describing her own recruitment story, back at the very beginning of Silk Road’s journey.

Why Wu Man and Joseph Gramley joined the Silk Road Project

WU MAN: The first time I met Yo-Yo. We played a lecture concert together. That was about: what is traditional, what is contemporary? What is East, what is West?

During that very interesting lecture concert, Yo-Yo told me he wanted to found this group called Silk Road. He said, “Well, I just want to have a band. The band is like mixed instrument, mixed musician, all from a different country, that kind of international band, so we can tour.” And then I look at him. I said, “Wow, that’s kind of my dream. That’s my mission. I want to do that too.” So of course I said, “Wow, let’s do it.”

HOFFMAN: Yo-Yo recruited Wu Man by sparking her passion for the mission — that is, to assemble a one-of-a-kind international band. Then Wu Man took that spark and recruited another key co-founder, percussionist Joseph Gramley.

JOSEPH GRAMLEY: I play basically anything you can shake, scrape, or strike. I was trained to play in an orchestra. I went to Julliard, and I should have ended up in an orchestra, and for a while, that was my dream, but as I started to play more instruments from around the world, I started to branch out and play a lot of new music, a lot of global music, a lot of world music.

We went to lunch one day. It was myself, the famous pipa virtuosa Wu Man, and the composer Bright Sheng.

We were at a table near the back, and that was when Wu Man mentioned this project I had never heard of. “Hey, Joe, we’re doing this project with Yo-Yo Ma, and we are interested in finding percussionists who play both Western and non Western instruments. Now, listen, Joe, there’s no pay, and you’re going to have to stay with a host family, maybe sleep in the guest room, maybe sleep on the floor. Would you be interested in joining us?”

I found myself two months later driving every instrument I owned — Chinese opera gongs, tam tams, which is just a massive gong, the marimba bars, they’re made of rosewood from Honduras. They were very delicate. I’ve usually rolled them up in a blanket, and I put them on the front seat, so I could take care of those two little bundles of joy. It’s a beautiful drive. Big blue sky, bulbous, round, full green trees up the highway. I could hear the rattle of the gongs and the tam tams in the back of the car. I was nervous. I was excited. I didn’t know what I had gotten myself into.

HOFFMAN: That feeling of “I didn’t know what I’d gotten myself into” is so familiar to entrepreneurs, leaping into the unknown. Yo-Yo was essentially asking these best-in-class musicians to co-found a startup. But their first proving ground wouldn’t be in a garage in Menlo Park, or a dorm room at Stanford or Harvard. Where Joseph was headed in his car full of delicate instruments was to the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, nestled in the Berkshire Hills.

The Silk Road Project’s first gathering

COHEN: Tanglewood, the first gathering of the Silk Road Project.

GRAMLEY: Tanglewood is an arts center in Western Massachusetts. They have now three or four concert halls. There’s a lake nearby. There are rolling hills. It’s absolutely beautiful.

MAN: Tanglewood. It’s like, oh, my gosh. As a young musician, just landed in this country, and playing this weird pipa instrument, and then wanting to go to a Tanglewood. It’s like a dream place, heaven.

MA: The Western musicians all volunteered. They were interested because they’re curious.

GRAMLEY: I arrived to Tanglewood, and I unloaded. And then I went to meet the bus. The bus hadn’t yet arrived from JFK.

MA: Drivers volunteers would get lost and finally get to the house at midnight.

GRAMLEY: And then I see, from about a hundred meters away, the bus turns into the parking lot, comes straight towards us, then parks right in front of all the people. It turns out these folks were our host families.

MA: We had no money, so people opened up their houses. This was like a family affair.

GRAMLEY: And then, people started to introduce themselves to each other. At this point, there was a massive language barrier.

MAN: I met so many musicians, composers from Mongolia, from Azerbaijan, China, Japan, Turkey, Iran — and so many musicians and composers there.

GRAMLEY: We went from there to a group picnic at one of the host families’ homes. There began just the process of getting to know each other.

MA: You know, my poor family. I have to apologize and thank them. Jill went out the day before and bought pounds of rice and rice cookers. The Mongolians, turns out, eat quantities of meat that you would not believe. Steaks, three pounders, gone. Sixteen eggs. Halal. There were non-meat eaters. People only eat rice. They’re in strange territory, so we have to win their trust. We have to give them the things that they operate from. And did we know? No. Did we find out quickly? Yes. Was it scary? Yes.

MAN: I can feel that happiness there. We know something’s going to happen. We’re going to try something very different.

HOFFMAN: What is so vivid in this story — besides the image of musicians tearing through heroic quantities of meat and eggs — is how Yo-Yo and his co-founders leveraged their networks to recruit people to the cause. Host families opened their doors. Drivers volunteered to make runs from the airport. And musicians hopped on planes and traveled halfway around the world.

This incredible gathering was only possible because each new team member reached out to their networks, recruiting more and more people to the mission. The result was a flywheel of excitement, gathering speed. It gave the Silk Road Project momentum as they headed into their first rehearsals at Tanglewood.

[Ad break]

Whether you’re a start-up, or a newly formed orchestra — once the team is assembled, the real work begins, and new challenges rise to the surface. That’s what you’ll hear as June leads us into this next segment.

How The Silk Road Project addressed language barriers

COHEN: The first terrifying rehearsal. How do you overcome group fears? Find a common language and listen for that transcendent moment.

MA: At Tanglewood, the great challenge was fear. The fear that it would be a disaster and that things would fall apart, it wouldn’t work, people hated the music, and it’s a bust. That would be a legitimate fear.

We had a lot of pieces to rehearse in 10 days. Tanglewood, they were very generous with giving us rehearsal space and barns.

MAN: Like, wow, how can we rehearse there? You’re just in this box. There’s no floor, it’s just dirt, it’s just the grass. It’s very much like summer camp.

First rehearsal was tough because there are a lot of different languages going on. We have so many translators as well. It’s like in, I don’t know, the UN.

GRAMLEY: The language barrier was something that we addressed on a case by case basis, depending on who was in the group and which common languages they might have. For example, I played in a group with Kayhan Kalhor, who’s Iranian. He had studied in Canada and spoke … his English was good at the time, but he also spoke Italian, and I spoke Italian, so we would use that commonality to then translate for other people. One of the violinists spoke Russian and English and that was incredibly helpful for the artists from Central Asia, because they had spoken Russian there. It was our way in.

MAN: After the worst rehearsal, all the mosquitos, I remember so clearly the first Tanglewood workshop, the mosquito just bit me the whole body, but that was so memorable, and that’s the happiest time for me. After a few days, we don’t need a translator anymore. The room started empty, and there started to be only musicians there. I was very moved by that.

GRAMLEY: I was in a rehearsal at the East barn, and all of a sudden, I heard this voice and a style of singing I’d never heard before. So we literally all stopped. It was the voice of Congrazole Gongbatar, a Mongolian long song singer who had such power that her voice went from the West barn all the way up to the East barn and forced us to stop our rehearsal. And we just listened.

MAN: Somehow we just communicate without language. We understand each other. That’s the beautiful thing.

HOFFMAN: This moment, where the need for translation stops and your team starts understanding each other fluidly is a magical one in any scale journey. It’s a moment every global business aspires to, as well as every coding team, design team, and product team.

When everyone in your organization is dialed-in on a mission, it helps every team member get on the same page. And the more everyone works together, the easier fast communication becomes.

But of course, even when your team is communicating perfectly, that doesn’t mean the road ahead will be smooth. Anytime you’re trying to innovate something the world has never seen before, there are going to be some setbacks.

Learning the music of The Silk Road Project

COHEN: How do you inspire a group to go beyond what they thought was possible? Honor every contributor. And laughter always helps.

GRAMLEY: A lot of times, if you’re not ready by the first rehearsal, it’s too late just because there’s such limited time to learn this music. I had the music now for about three weeks. I was playing six new commissions. The majority of the pieces had multiple percussion instruments.

I would practice late into the night. I’d get up in the morning before rehearsal to practice my parts. I was a little anxious about if I was going to be good enough, if I was going to be able to keep up with artists that Yo-Yo Ma had selected.

MAN: You have to learn the piece quickly, and some pieces are very contemporary. It’s just very microtonal, very new, it’s so hard.

GRAMLEY: The music was really hard. These composers who Yo-Yo commissioned really threw a lot at us. So the notes were hard; the notes were fast. I’d never played in ensembles with these instruments. I had never heard of some of these instruments.

MAN: And also play with so many different people from different countries and different instruments, which a lot of instruments you never see before, that’s quite challenging.

MA: We wanted to honor traditions. Persian tradition is very specific. Mongolian long song tradition is very specific. It’s amazing. Also very loud.

MAN: The pipa sounded very different with this huge percussion and how we balanced.

GRAMLEY: Now I need to balance my sound with that instrument. I need to morph and merge my groove and my time with artists who have a different sense of groove from their culture. We had to find the musical connection to successfully bring to life the visions of the composers. That was the hardest thing. There were moments when one might think, this is not going to work. You might be panicked. You might be in the middle of a piece of music, and you have to stop because people are in different places, and you’re never going to get back on. A lot of my training in chamber music, in Western classical music, comes from the musical score, and you study the score, and then if there’s an issue, you can jump to where that is. Not possible with the music of Silk Road because it’s so new.

The first open rehearsal was in the brand new Seiji Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood. That was a dry run. Mostly, it was the host families, maybe 75 to 100 people, all seated up pretty close. It was a very relaxed atmosphere. There was a lot of laughing, but there were more than a few times where folks had to stop or someone would look across the ensemble, and someone was in a completely different spot, and they’d have this moment of, “uh, what do we do? Who do I go with?” And we smiled, and we laughed, and Yo-Yo would say something funny and bring us all back together.

MA: Not having control of your environment and somehow staying focused and resilient. If you control something too much, you’re delivering a product, and that’s not what live performance is about.

HOFFMAN: If you’re listening as an entrepreneur, what Yo-Yo just said might sound a bit strange. Because the “product” of the Silk Road Project was, in fact, the live performance! Including all the imperfections and hesitations along the way.

When Yo-Yo says the word “product,” what he means is something that feels manufactured and uniform. And in any field, when you’re building something new, there’s tension between creating a structured and stable environment for your team, and leaving room for accidental discoveries. Too much control, and you stifle innovation. Too little, and you risk falling into chaos.

You can hear how that tension continued, from the “dry run” rehearsal into Silk Road’s first performance for the general public.

GRAMLEY: We had grown close over two weeks. We had struggled with the music. We had worked really hard.

MAN: You have to learn many pieces in 10 days. And then on the last day, you have to present those piece in the concert with a public audience, and they’re all musicians. That’s kind of nervous, like college exam day.

MA: At the end, we were having all these managers and presenters come in from around the world to create a moment where we can actually show what these things were.

GRAMLEY: Managers were there, agents were there, conductors were there to hear this music for the first time. What was at stake was a belief that this music needed to be heard and that if we didn’t play it well, we might lose the opportunity to play it again. If we played the music well, would people accept it? Would they want to hear more of it? To see if it could tour.

MA: They’ll have to figure out how to market this idea for their local audiences to see whether we were trustworthy enough to make the leap.

HOFFMAN: The Silk Road Ensemble had done their best, and gone on a series of sprints to get ready for the performance. They were about to debut their minimum viable product to the music world. Everything was on the line.

And it’s at this moment that we’re going to leave their story. To find out what happens next, subscribe to Spark & Fire, presented by WaitWhat. You can hear the full Silk Road episode, and others by legendary creators, telling their stories of their most iconic works. Each lesson is its own study in scrappiness and grit, applied to fields we don’t always get to cover on this show, from graphic design to stand-up comedy.

Season 2 is out right now. Spark & Fire is a WaitWhat original in partnership with the BBC.

Find the link in our show notes, or at sparkandfire.com.

I’m Reid Hoffman. Thank you for listening.