Building a bridge over troubled waters

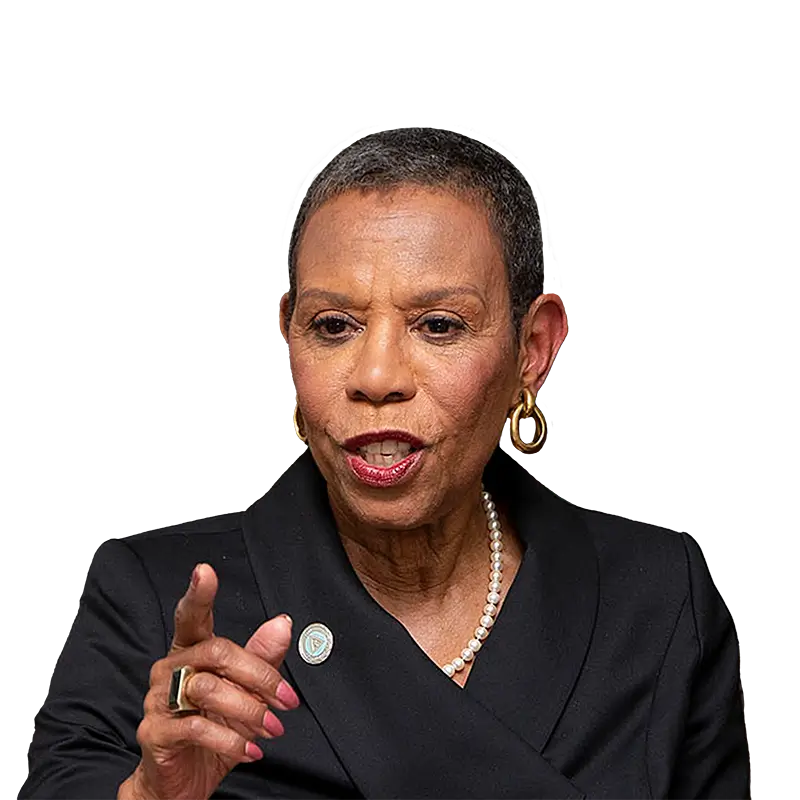

How to keep a university’s doors open? This is the question for Dr. Mary Schmidt Campbell, president of Spelman College. In summer 2020, Dr. Campbell announced Spelman’s plan for the new academic year – with many fewer students on campus. Meanwhile, as the head of a historically Black college, she’s grappling with social unrest and calls for change.

How to keep a university’s doors open? This is the question for Dr. Mary Schmidt Campbell, president of Spelman College. In summer 2020, Dr. Campbell announced Spelman’s plan for the new academic year – with many fewer students on campus. Meanwhile, as the head of a historically Black college, she’s grappling with social unrest and calls for change.

Transcript:

Building a bridge over troubled waters

MARY SCHMIDT CAMPBELL: Spelman College produces more Black women who complete PhDs in STEM fields than any other college or university in the country, and we do that with a fraction of the resources. So imagine if in fact this country were to begin to make those investments equitably, how much more we could do to further the college completion rates for our community?

Here we are now 50 years later, and we’re still dealing with the same issue. We’re here in Atlanta, and the first incident was the Ahmaud Arbery incident. Then the death of George Floyd in front of your eyes was so painful, and that coupled then to hear about Breonna Taylor soon after that. And then the two college students who were pulled from their car and tased and thrown to the ground, one of them was a Spelman student. It felt like one of my children had been harmed by the excessive force that we’ve seen over and over and over again.

Tomorrow is completely uncertain. You wouldn’t invite 600 young people to come into your city, knowing that if they get sick, they might not be able to get adequate care.

For my Spelman students, we give them a way of determining who they are – what is your identity or identities? You can be a Black woman. You can be a gay Black woman. You can be a top-level mathematician. You can be all of those identities. You can shuffle them around. You can change them.

The idea is that we want you to have the freedom here to discover yourself intellectually, discover the things that make you passionate and joyful when you wake up in the morning, and the way that you want to live your life after you leave here. So I really think it more, if I’m a model of anything, I’d like to be a model to my young women, to have that freedom to be able to discover their true self.

BOB SAFIAN: That’s Dr Mary Schmidt Campell, President of Spelman College. Dr. Campbell made the difficult decision in the spring to close Spelman’s campus. As fall approaches, she’s set in motion a novel plan that will have only 30% of students on-site.

At the same time, her faculty is recasting parts of the curriculum to reflect this moment of social upheaval. I’m Bob Safian, former editor of Fast Company, founder of The Flux Group, and host of Masters of Scale: Rapid Response

I wanted to talk to Dr. Campbell because her challenges straddle the academic, the social, and the financial in unique ways. And her experience at the helm of a historically black college give her a perspective we can all learn from.

When Mary talks about “stories that would chill your blood,” she’s not just talking about George Floyd but about a Spelman student who was tased this spring and episodes that her own sons and husband have experienced.

She also talks about what she calls “a truly historic gift” from the Netflix founder and the effort she sees at companies like Microsoft to “move the needle.” She calls this era “a bridge over troubled waters.”

[THEME MUSIC]

SAFIAN: I’m Bob Safian, and I’m here with Dr. Mary Schmidt Campbell, the president of Spelman College. No organizations have faced more complex challenges during the coronavirus pandemic than educational institutions. Earlier this month Dr. Campbell announced Spelman’s plan for the upcoming academic year – nothing about it is business as usual. Meanwhile, as the leader of a prestigious, historically Black college that’s based in the protest hotbed of Atlanta, she’s also been grappling with this moment of social unrest and change. Mary’s coming to us from her home in Atlanta, as I ask my questions from where I’m currently sheltering in New Jersey. Mary, thanks for joining us.

CAMPBELL: It’s good to be here, Bob. Thank you.

SAFIAN: There are so many intertwined issues and challenges on your plate as the environment continues to move around on the health front, the social justice front, other areas. I want to start with COVID-19, when the coronavirus first hit, you quickly moved Spelman to remote classes. How difficult was that initial decision period?

CAMPBELL: I remember very vividly. I had been traveling before we made the decision. I had been in New York City. I had been in Philadelphia. I had been in Maryland. And it was clear with each trip that the virus – which at first seemed very distant, seemed to be something that first China was coping with and Europe was coping with – that the virus had arrived on our shores. And it was very clear that its growth was going to be exponential.

So by the time I got back to Spelman’s campus, it was spring break, and we made a decision very quickly that we would need to evacuate the college and transition to remote learning for the rest of the semester. And you may recall at the outset, there were some schools that were saying, “Well, we’ll do this for two weeks, and we’ll come back.”

It seemed pretty clear to me, if you looked at the predictive modeling for the way the virus was spreading, that this was going to get a lot worse before it got better. So I think it was to our advantage to make a definitive decision, which meant that we could get right to work with looking at what was needed in order to take the 800 courses we were teaching in person and transition those to online for our faculty, to look at what our student body required – because when they left, they’d have no access to our computer labs, to our mobile devices, to our internet access, what they would need in order to receive this online instruction. So it was a big disruption, but it was an opportunity for us to really begin a process of rethinking how we taught, what support mechanisms we needed. That began a conversation that frankly is ongoing to this day.

SAFIAN: It’s tricky because on the one hand, I know you’re eager to have students and all the faculty back on the campus. And on the other hand, there’s an opportunity maybe to think about the whole way education and colleges have worked differently in light of the new technologies that we’ve had available.

CAMPBELL: Well, that’s certainly true. And for us, the urgency is that Spelman is a historically Black college. It’s a college for Black women. We have 2,000 students, 96% of them are African American. Our workforce is overwhelmingly African American. And COVID is a disease, which, if you are infected by it and you belong to the African American community, the threats and risks for you are very real and very high. So we were driven by the need to make decisions on behalf of the health and welfare of our students and our workforce. And so that was overwhelmingly what drove us as we began to think about, “Well, what comes next?”

And then right after that, right behind that, were a set of considerations for, okay, we provide this extraordinary experience when you come to Spelman: relationships with faculty, with mentors, with peer-to-peer relationships, student groups, study abroad, all of these things. So we said to ourselves, “Okay, so you can’t have those experiences in real time anymore. What are the surrogates? What are the ways that we create community? What are the ways that we establish this sense of sisterhood, which is so much a part of what Spelman College is?”

And we began to see some of these solutions emerge almost organically. And that sort of organic evolution coupled with some really serious design thinking, I think, is going to serve us well, because I think we’re going to come up with some new and interesting and exciting ways to deliver our educational content.

SAFIAN: So I know your plan for the next academic year: freshmen come back – if everything holds – freshmen come back in the fall, but they’re the only class that’s on campus, right? Everyone else is remote.

CAMPBELL: That’s right, except with the exception of international students and the exception of ROTC, because our ROTC students have a whole number of requirements that require them to be physically present.

SAFIAN: But you made the decision that you needed lower density on the campus. And this was sort of the bargain you made about who gets to be on campus now.

CAMPBELL: Yes, that’s right. In the first semester, in the fall semester, about 25% to 30% are on campus. Everybody else is remote. Then the second semester, if all goes well, we have our freshmen and our seniors. And that comprises about half of the Spelman population.

SAFIAN: I know you worked with a consortium of other Atlanta-area schools in coming up with this system. Did you talk to a lot of other schools?

CAMPBELL: We looked at so many different plans, I can’t tell you. I mean, obviously, we’re part of a consortium, the Atlanta University Center Consortium. It’s made up of Morehouse College, which is an all-Black men’s college, a liberal arts college; Clark Atlanta University, which is a research university; and Morehouse School of Medicine. And it’s really helpful during a public health crisis to have a school of medicine as part of your consortium, trust me.

And we looked at all of their plans. We looked at plans throughout Atlanta, and we looked at plans throughout the country. We belong to a group called the Associated Colleges of the South. We know all of the plans of all of the colleges that belong to that organization. I think we must’ve looked at 50 plans – but it was really important for us to understand what is unique to Spelman and what makes the most sense for us.

So for example, Spelman has a very small campus. It’s 39.4 acres, say, compared to Georgia Tech, which is 400 acres, right, or Emory, which is 600 acres. So we knew then, just given the physical size of our campus – the number of residence halls we have, the size of our classrooms, our dining hall facilities – having everybody back was impossible if we also were to maintain physical distancing. So that was just impossible.

And we actually did just a calculation of, well, what would be the upper limit for the number of students? And I think it’s something like 629 or 640, but it’s somewhere in that neighborhood and with only a portion of our workforce coming back to work in person as well. So that understanding, I think, it was very important for each college to understand, who are you? What are your resources? What is the reality of the situation you are living in? And so we did what we thought was best for the realities of Spelman.

SAFIAN: Yeah. There’s some dialogue about, “Shouldn’t all schools have like a unified approach? Should everyone be acting the same way?” You’re laughing. That’s just not practical, right?

CAMPBELL: I think that is so utterly impractical because you really do have to give some consideration to the fact that this is a public health crisis that depends for its preventative measures on physical distancing. It depends on wearing masks. It depends on periodic testing. It depends on your ability to isolate when somebody tests positive and quarantine them. So if that’s what it requires, then you have to really assess, what resources can I bring to bear to make sure I’m able to do that responsibly?

SAFIAN: I want to ask you about the financial implications of all of this. One of the previous guests on this podcast was the CEO of Delta, which is a local Atlanta-based institution, and they’re spending a lot of time and money cleaning every plane and putting in hospital-grade air filters, which I’m guessing you would love to do with all your classrooms. But they’re also losing $30 million a day, right, which is probably not practical for you. How do you balance sort of the financial implications of some of these choices and the long term financial health of the institution?

CAMPBELL: That’s a huge question for all of us, for all colleges and universities, particularly one like Spelman, because we are tuition-dependent. Almost 50% of our budget comes from the tuition and fees that students pay us. The next big chunk of our income comes from room and board, $10 million a semester. So when we looked at what we could do in terms of low density, and you realize you can only have 25 to 30% of your population on campus, that’s a reduction of 70% for that semester in your room and board fees.

SAFIAN: It’s not like your costs are going down by 75%. Instead, they’re going up, right?

CAMPBELL: I’m not going to lay off 70% of my faculty, right? There are so many fixed costs: you have faculty and staff, you have buildings and grounds. Maybe your heat and light are not as high, but they don’t go down 70%. That’s for sure. So what the college had to do is we had to look very, very hard at those expenses that we could cut or simply eliminate.

It was a process that we undertook with a great deal of collaboration with our faculty and a great deal of collaboration with our staff, and with a real understanding on the part of our community that we were doing this as, what I would call, a bridge over troubled waters. We all understood at some point this is going to get better and we’ll be in a place where we can resume having people back on our campus but for now, we’re just going to have to make some sacrifices. The toughest ones that we had to make, we had to furlough faculty and staff. That’s a really tough decision for a college to make.

[AD BREAK]

SAFINA: You built your plan before the recent surge in cases, in the South and in other places in the country, how do you track what’s going on? Are there adjustments, reconsiderations that are on the table?

CAMPBELL: A group of us on our senior leadership team who get these reports of the rate of infections – and they’re done state by state, and then within states they’re done county by county – and we get those reports every day and we check them. What we’re looking for is if by the time within two weeks, three weeks of our opening, if we see a surge in cases and particularly, a surge in hospitalizations, we think it would not be responsible for us to bring people back, because if there were to be an outbreak and the hospitals are at capacity, what would we do with students who become ill?

For me, I think it’s a deeply moral decision. You wouldn’t invite 600 young people to come into your city, knowing that if they get sick, they might not be able to get adequate care. So we keep a very close eye on that and, in our minds, we know that there may be a time when we may have to pivot and reverse our decision.

SAFIAN: A lot of students, of course, are eager to get back to campus and so may be willing to take certain risks that maybe older faculty members may be more anxious about. What feedback have you gotten about the plan from students, from faculty? Is it consistent?

CAMPBELL: Overwhelmingly, I would say our students are more eager to come back. I think for the reasons that you cite. I mean, statistically, young people are less likely to, if they get sick from COVID, to have a serious illness. They’re more likely to recover and recover without lasting effects. Faculty, on the other hand, feel that it’s a high risk situation. Most faculty, I don’t know the exact statistic, but I’m willing to bet most of my faculty are over 50 and maybe a significant portion over 60, so these are the high risk areas.

We know that about 47% of our workforce has an underlying condition that marks them as high risk. We know that many of our students coming in will have underlying conditions – they’ll suffer from asthma, they’ll have diabetes or hypertension – so we feel very strongly that attention to the health and wellbeing has to be uppermost in our mind, given the demographics of our students and our workforce.

SAFIAN: You did the furloughs, were they voluntary?

CAMPBELL: We chose the amount of days for furloughing based on salaries. So if your salary was $40,000 or less, you were not furloughed at all. And then the first tier was, I think, furloughed for five days and the tiers go up to 10 days and then 15 for the senior team. That’s the president and her cabinet. I think they were about 10 or 12 of us, and we have the most days to be furloughed.

SAFIAN: Yes, and I’m sure you’re taking all of those days off.

CAMPBELL: I’m laughing.

SAFIAN: All this is in the context of, of course, social action and upheaval. When did you first hear about George Floyd’s killing and how did you respond?

CAMPBELL: So you have to remember that we’re here in Atlanta, and the first incident was the Ahmaud Arbery incident, and that was just so shocking. Just the idea of somebody jogging and being almost hunted like prey, that was chilling enough. Even to this day, to watch the death of George Floyd in front of your eyes was so painful, and that coupled then to hear about Breonna Taylor soon after that. And then for us, you may recall that the two college students who were pulled from their car and tased and thrown to the ground, one of them was a Spelman student. The incident happened on a Saturday night, and I called her on Sunday morning and I spoke to her, and I said, “What happened?” And she told me the story.

Honestly, when I finished speaking to her, I was shaking. It was absolutely harrowing to hear what had happened to her. It felt like one of my children had been harmed by the excessive force that we’ve seen over and over and over again.

I have a personal issue with this particular set of recurrent episodes of violence. It made me recall when I saw that in Philadelphia, they were pulling down the statues of Frank Rizzo. My father had been involved in a lawsuit against him, and I looked it up and sure enough, in 1969, he was part of a group of attorneys who filed suit against Rizzo and the Philadelphia Police Force, for what? Excessive force.

In those days, and this is an interesting historical contrast, in those days, Rizzo, as police chief, was defiant and felt that was a badge of honor and was eventually elected the Mayor of Philadelphia. So here we are now 50 years later and we’re still dealing with the same issue.

Also, I have three sons and I’ve been married for 52 years. We could sit here all afternoon, and I could tell you stories that would chill your blood about the encounters that my children have had or my husband has had. Now, who are these children? The oldest one has a PhD in theoretical mathematics. He’s a provost at a state university in North Carolina. The second one is an attorney. The third one is a Lieutenant in the United States Navy. My husband is a physicist and a former college president. What a danger to society they are. But each and every one of them has had that kind of experience.

So to see this was to see a coming to a head, so to speak, of events that are part of our history and part of our experience. What was different, or what seemed to be different this time, is that there was an awakening on the part of people outside of the Black community who saw what we were seeing as well. So it felt like after telling that story over and over and over again, and sort of saying, this is really not right, finally, there was an opportunity for a larger community of really concerned and dedicated citizens of all stripes to say, “I see this, I hear this. This is not correct. We need to do something different.”

SAFIAN: Are there things that you think are going to be different at Spelman this year and the years ahead as a result of this, or is this more about externally communities outside of Spelman, how they might react to Black Americans differently?

CAMPBELL: As you know, we were the recipients of a truly historic gift from Patty Quillin and Reed Hastings. And one of the things that a gift like that did was train lights on a place like Spelman and Morehouse and UNCF, United Negro College Fund, which represents 37 HBCUs. I think one of the differences is that things we have been saying about closing the educational equity gap, things we have been saying about economic inequality, things we’ve been saying about health disparities for years, the research that we’ve assembled for years, the books that have been written for years, I think finally, we believe that those narratives are going to be heard now.

And so at Spelman, our faculty, our students are opening up opportunities to have conversations, difficult conversations, about difficult issues. Our faculty has taken our whole first-year curriculum for our interdisciplinary courses and has put together topics for our first-year students to consider the difficult issues that the country is facing, like should we defund the police? And having those conversations within the curriculum, outside of the curriculum, with the community, with our local community, with the national community, I think we are inspired because we know those conversations are going to be meaningful, not just to us, but to a wider circle.

SAFIAN: Lots of businesses these days are talking about new commitments to being anti-racist. What do you think the role of business is in this change that we’re going through?

CAMPBELL: I had the opportunity recently to read a statement by the CEO of Microsoft, Satya Nadella, and I was very struck by the extent to which he clearly had sat down with his leadership at Microsoft and clearly had had conversations with his workforce and came up with a plan with targets and dates and timetables for ways in which he was going to rethink Microsoft’s relationship to various aspects of the Black community.

Again, the donors who made that wonderful gift to Spelman and Morehouse and UNCF, I was struck by the fact that Netflix has made striking progress in terms of diversifying its workforce over the past few years. Its programming is probably the most diverse that you can find either on television or in streaming today. They just announced that they’re investing, I think it’s one hundred million dollars in Black banks.

So I look at companies like that and what I see is a really definitive effort, not just to throw money at something, but to think through “Where can I make investments that are really going to, five years down the road, make a significant change and move the needle?”

SAFIAN: What’s the role of academic institutions in a time like this? And is it different for a historically Black college and university than for another higher education institution?

CAMPBELL: I always hesitate to provide any critique to other people’s institutions, but I will say that I went to a predominantly white institution. I sat on the board of my alma mater for 12 years, and I was at New York University as a dean of the school of the arts for 23 years. And my husband, as I said, was a college president as well. So I feel as though I do have an experience with small liberal arts colleges, big research universities, and have a sense of where they can make a real difference. One of the things that I find very striking about a lot of predominantly white institutions is that if you look at the percentage of Pell eligible students whom they admit, who complete their degrees, it’s tiny by comparison with the number of Pell eligible students that HBCUs admit, enroll, and graduate. If you’re eligible for a Pell grant, it means that your family makes an annual income of $40,000 or less.

That entire amount of the total annual income is less than one year of Spelman’s tuition room and board. So in fact, you’re talking about families for whom there has to be a whole network of financial support. Even if they’re the smartest, most gifted, hard working students, they need a network of significant financial support in order to get through that four years in college and leave without being saddled unreasonably by debt. And what it says is that HBCUs have been taking on this responsibility, and we welcome that. Where I think we feel as though the philanthropic community and to a large measure the federal government has come up short is in making investments in us, so that we can in turn assist those students in making their way through.

So I think that it’ll be very interesting to see, moving forward, the extent to which – and I think that this is happening – the extent to which people are beginning to recognize the value of HBCUs in terms of how they’re taking on this responsibility and how much they’re willing to invest in their ability to succeed. And we know that they’re succeeding because if you look at National Science Foundation statistics, and you look at fields like physics, engineering, math, computer science, and you look at the top performers, the colleges that are graduating the most Black students in those areas, they’re almost always HBCUs. Spelman College produces more Black women who complete PhDs in STEM fields than any other college or university in the country, and we do that with a fraction of the resources. So imagine if in fact this country were to begin to make those investments equitably, how much more we could do to further the college completion rates for our community.

SAFIAN: It does seem like in the educational realm, as in so many other parts of our culture, those who have resources seem to have an easier time getting more of them. When you look at those realities, does that frustrate you?

CAMPBELL: I think it did when I first came to Spelman and I’ve been at Spelman for five years. And of course, Morehouse is right next door, and Clark Atlanta, and I got to know more and more about them. I thought, “Oh my goodness. Why are we a secret? It must be that people don’t know.” So maybe the answer is that let’s get out and tell everybody about these colleges, because surely if they know that we are realizing these academic outcomes, surely if people knew, there would be just a surge of donations.

But I will say that it was a slow process. I have seen the beginnings of a change. Spelman has a wonderful set of really loyal and passionate supporters. And it is true that the more we were able to show them and demonstrate quantitatively and qualitatively what their investment was reaping, we began to see these changes. What I think is happening now is I think there’s an opportunity for a wider circle of people to see what the return on their investment would be were they to make these investments in HBCUs.

SAFIAN: Many Black leaders face a lot of pressure, not just doing their jobs and managing their family and their emotions and their health, but also constantly being a role model standing for other things. Do you feel that pressure and that stress and how does that historical reality go into the training you give for your students?

CAMPBELL: So Bob, I’m going to share a secret with you: I’m 72 years old. So I’ve been around for a long time. And I recall early in my career hearing the phrase “role model,” “role model,” and I was always not real comfortable with it. To say that someone is a role model says that there is a way of being successful. There is a model and perhaps you should be molding yourself to fit that model.

In point of fact, I came to my profession, which is art history. I didn’t know very many Black art historians. I was a curator, I knew even less curators. And my first professional job was as a museum director. I knew no Black museum directors. So I’m always a little wary about that term, “role model.” What I would prefer is that for my Spelman students, that we give them a way of determining who they are – what is your identity or identities? You can be a Black woman. You can be a gay Black woman. You can be a top level mathematician. You can be all of those identities. You can shuffle them around. You can change them.

The idea is that we want you to have the freedom here to discover yourself intellectually, discover the things that make you passionate and joyful. So I really think it more, if I’m a model of anything, I’d like to be a model to my young women to have that freedom to be able to discover their true self.

SAFIAN: You don’t seem very stressed by all these things that have gone on this year. Is that because you feel like you’ve seen it all, or you’re just plowing through and trying not to focus too much on the uncertainty in it?

CAMPBELL: I do have moments of real stress, there’s no question about that, but I will say that we have tried very hard at Spelman – and by we, I mean, not just me, but my senior leadership team, the faculty we work with, the students. We really try to create what I call, a culture of caring, where we can feel relaxed, open and honest with each other. I can make a mistake. I can say to my team, “Oh, you know what? That really wasn’t a good choice. Let’s rethink that.”

And they can feel the same way with me, because I think that what we’ve discovered is that when we’re able to work in that kind of close knit, collaborative way, in a way that enables us to make mistakes, fail, try again, having a growth mindset, so to speak, that we can find our way through this. We may not start out having any idea what the answer is, but if we stick to this and we’re working on this together, we’ll figure our way out through to the end of this. And I think having set that tone and way of working, I feel that I’m surrounded by people, all of whom are committed to this mission and committed to Spelman succeeding and we’ll make a way out of no way.

SAFIAN: Have you learned things about yourself, your colleagues, your institution, going through the challenges that we’ve seen in the last few months?

CAMPBELL: Absolutely. I have learned that people sometimes have an extraordinary reservoir of talent. That in the course of day to day, doing your work, may not manifest itself, but in a crisis, sometimes that’s when people show gifts that you’ve never seen before. If you’re alert to people demonstrating their real strengths or coming forward with new ideas and new ways of thinking things, if you allow for that, you can really reap this incredible harvest. It’s been really interesting to see people who may have been quiet, speak up. People who have been doing the same thing over and over again, who all of a sudden have a bright idea about something completely different. If you let it in the room, it’s going to energize and contribute to everything.

SAFIAN: So given all the dislocations right now, what’s at stake for Spelman? For Spelman’s present? For Spelman’s future?

CAMPBELL: I think that what is at stake is making sure that we have a way of guiding our students over that bridge. I talked about trying to build this bridge over troubled waters. I think we have to give our students a sense of confidence that we are going to be there with them, hand in hand, and we’re going to get them over this. We’re going to get them through this. This is a tough time for all of us and for all of our families. I have students who have themselves been victims of the COVID virus. I know of family members our students have lost, their families have lost jobs. They’re under incredible financial constraints. The whole online learning environment is new for them. So gaining a deeper understanding of what they’re going to need in order to get through, I think that’s what’s at stake, because we want to keep them on track academically. We want to keep them whole emotionally. We want to be able to get them there. That’s number one important to us.

Number two, is we have to be fiscally sustainable. We’re not a multibillion dollar endowed institution. So we have a healthy endowment, but we’re not wealthy. We have a teeny tiny reserve that doesn’t come anywhere near what the financial losses will be for us this year. So to make sure that we have the discipline and the resources that we’re going to need in order to keep ourselves in balance, I think is going to take a great deal of vigilance on our part.

SAFIAN: Your first answer is about taking care of your students, which is today. The second answer is about taking care of the institution, which is tomorrow. In some ways, the tomorrow is harder to control.

CAMPBELL: I mean, the tomorrow is completely uncertain. I think that’s what has been the most challenging part of planning. When we sat down three years ago to do our grand strategic plan for the college, we planned with an idea that, “Well, there’ll be some change, what have you, but basically life will be pretty much the same for the next five years with some variations.”

Now when we sit down to plan, we don’t know what’s going to happen a week from now. That level of uncertainty has kept us very much on our toes. I think one of the things we’re watching out for is to make sure that everybody who’s part of this planning has time to step out, rest, take a deep breath before they come back in. So now we’re being very vigilant to make sure that people are taking their vacations, that when they do leave, we don’t pester them. We tell them to turn off their devices and really step away, because that’s a vulnerability as well, that people just say, “When does this stop?” Because it just seems that we just have to be so alert all the time, because things are changing. That is one thing that we have to watch over very, very carefully.

SAFIAN: Well, Mary, this has been great. Thank you for taking the time. I really appreciate it.