How to turn intentions into action

In May 2020, as companies began making promises about how they’d help Black-owned businesses, Aurora James launched the 15 Percent Pledge with an Instagram post. Tagging major retailers, she declared that 15% of retail shelf space should belong to Black-owned businesses. Learn the tactics and strategies that allowed one small, dedicated effort to unlock $10 billion in revenue.

In May 2020, as companies began making promises about how they’d help Black-owned businesses, Aurora James launched the 15 Percent Pledge with an Instagram post. Tagging major retailers, she declared that 15% of retail shelf space should belong to Black-owned businesses. Learn the tactics and strategies that allowed one small, dedicated effort to unlock $10 billion in revenue.

Transcript:

How to turn intentions into action

AURORA JAMES: She was like, “They just donated a couple million dollars to the NAACP. They love the Black community.” And I was like, “Really? Is that what it means to love the Black community?

By day 10, Sephora became the first major corporation to commit to the 15 Percent Pledge. And since then, we’ve announced 28 major corporations as pledge takers, and we’ve taken over $10 billion and diverted that to Black-owned businesses across this country.

I would be lying if I didn’t tell you that it’s really, really hard. For all of the companies that have taken the Pledge – Ulta Beauty, Rent the Runway, CB2, Hudson’s Bay – there are a lot of other companies that haven’t taken the Pledge.

Everyone has told me my whole life that things were going to be impossible. I’m constantly surprised by how wrong people are.

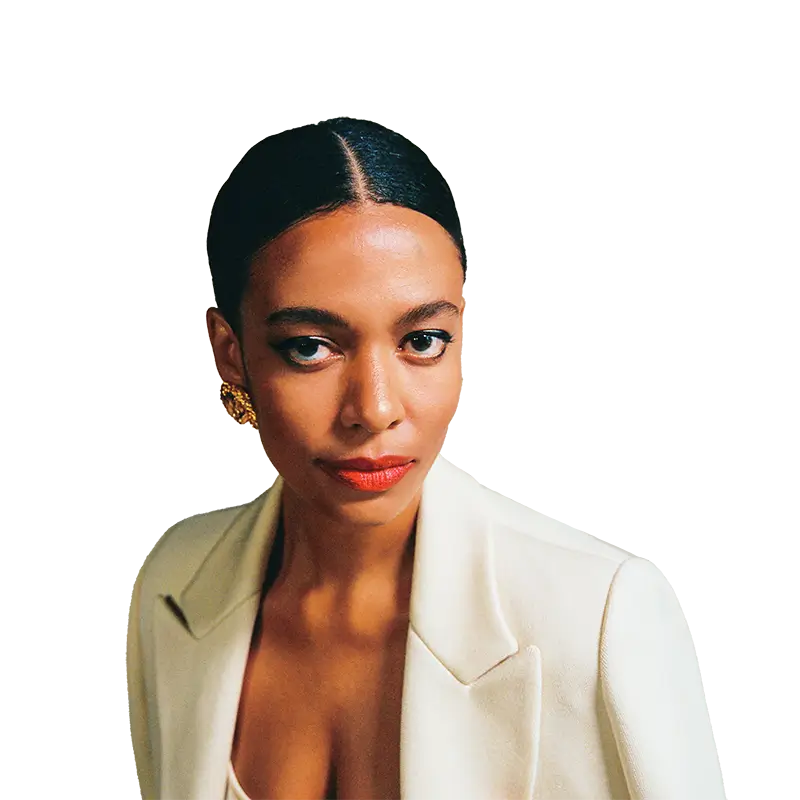

BOB SAFIAN: That’s Aurora James, fashion designer, entrepreneur, and founder of the 15 Percent Pledge.

When companies began making promises after Goerge Floyd’s killing about how they’d help Black-owned businesses, Aurora stepped in to turn that impulse into tangible impact

I’m Bob Safian, former editor of Fast Company, founder of The Flux Group, and host of Masters of Scale: Rapid response.

I wanted to talk to Aurora because while the outcry over Black under-representation in business and entrepreneurship has receded from headlines, the need remains as acute as ever.

Aurora’s 15 Percent Pledge has shown how good intentions can be solidified into action and improved business outcomes, on store shelves from Sephora to Ulta.

She’s found creative ways to engage Google, Vogue, and others, deploying an entrepreneurial playbook, as well as clear data to leverage change .

At the same time, Aurora has had to navigate obstacles for her own business, when the pandemic brought things to the brink.

But her steadfast optimism has carried her through, a testament to how one small, dedicated effort can deliver outsized results.

[Theme music]

SAFIAN: I’m Bob Safian, and I’m here with Aurora James, founder of the 15 Percent Pledge and founder and creative director of sustainable fashion brand Brother Vellies. Aurora is coming to us from Brooklyn, New York, which is also my home base. Aurora, thanks for joining us.

JAMES: Hi, Bob. Thanks so much for having me.

SAFIAN: So since the pandemic hit, like many entrepreneurs, you’ve had to make a bunch of pivots and adjustments at Brother Vellies. And in the midst of that, you also launched a nonprofit, kind of by chance, by accident, I’m not sure how you describe it. But you initiated an effort in support of Black-owned businesses that became known as the 15 Percent Pledge, holding some big retail brands accountable. I’d love to start with the 15 Percent Pledge. Can you explain what it is, and then take us through the story of how it came to be? It all started with just an Instagram post, is that right?

JAMES: Exactly. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, I was getting a lot of calls and texts from people that were like, “What should we do? How should we respond as a company? Who should we donate money to?” And listen, it was a really difficult time for all of us.

We were in the middle of a global pandemic. And at the same time that I was getting these calls, as a consumer, I was getting all of these newsletters that were saying like, “I support Black Lives Matter, and we stand with you.” And I was understanding what they were trying to do, but it really wasn’t resonating with me as a human. I just needed companies to do more.

A friend of mine called and was talking to me about a major retailer. And she was like, “They just donated a couple million dollars to the NAACP. They love the Black community.” And I was like, “Really? Is that what it means to love the Black community? And of course, a million dollar donation is wonderful and super appreciated. But if we’re talking about a company actually being anti-racist and wanting to stand with the Black community at that moment, I think it calls for something more. And she was like, “Well, they’re a major retailer, what would you want them to do?” And I was like, “Well, Black people in this country are almost 15% of the population. They should consider committing 15% of their shelf space to Black-owned businesses.”

And she was like, “I don’t think anyone can do that.” And I was like, “All right, cool. Let’s get off the phone then.” And I sat there on Saturday and quarantined in this apartment in Brooklyn and really thought about that proposition and what it would mean. As a founder myself, I knew at that time that we were estimating over 40% of Black-owned businesses to be closing during the pandemic. I knew how tough it was for all small businesses in America, but seeing that the Black community was being hit especially hard. And I knew what kind of value proposition that would mean for them if major retailers committed to that.

So I just sort of sat down and wrote it out on my notes on my phone and posted it to Instagram an hour later. And Sunday, I stayed up overnight with my web designer. We launched a petition Monday at noon. And then Wednesday, we became a nonprofit. And by day 10, Sephora became the first major corporation to commit to the 15 Percent Pledge. And since then, we’ve announced 28 major corporations as pledge takers. They’ve all signed contracts with the nonprofit organization, and we’ve taken over $10 billion and diverted that to Black-owned businesses across this country.

SAFIAN: When you first heard from Sephora, the first one, were you like, “Oh my goodness, this is actually working?” What did you expect to happen?

JAMES: Yeah. I mean, listen, Bob, here’s the problem with me. Before I ever was on the Time 100 list, I was on the Time optimist list. So the optimist in me said, “I’m going to put this ask out there into the world. I’m going to ask major retailers to commit 15% of their shelf space to Black-owned businesses. And I believe wholeheartedly that someone will answer my request and say yes.” So I was really optimistic, and I tagged the companies that I thought would be best suited to rise to the occasion.

I tagged Sephora, I tagged Target, who unfortunately hasn’t taken the Pledge, I tagged Medmen. The cannabis industry, of course, needs to show up in a meaningful way. They also took the Pledge. And the rest, as they say, is history.

SAFIAN: So during that time, there were a lot of businesses that made announcements. “We’re going to do this for the Black community, and we’re going to do that.” And there’s some question about, well, what’s the longstanding impact of that going to be? So how do you think about this idea of sort of pledges versus action versus really making something happen?

JAMES: Well, great question. So I, of course, already had a full-time job running Brother Vellies, right? But I knew that if I was going to ask these major retailers to pledge in this way, I was also going to have to be responsible for holding them accountable, right? And that’s why I launched the Pledge, not just as an idea, but as a nonprofit organization. And when we talk about Nordstrom, for example, they signed a 10-year contract with the 15 Percent Pledge. So every quarter, we’re actually sitting down, doing an audit with them, looking at how their shelf space is growing, what have been the pain points, making recommendations of Black-owned businesses for them to onboard, and really figuring it out because, exactly what you said, Bob, there were a lot of commitments that were being thrown around. And I really wanted to make sure that we could actually pull it out into long-term, meaningful change that was going to put actual money in the hands of Black American entrepreneurs.

SAFIAN: You guys did a survey at your one-year-anniversary, the collective impact survey. And was that part of the effort to quantify and keep this impact moving forward?

JAMES: Absolutely. I think, for me, what was important was doing something that was going to actually have a data set next to it, right? So we were able to say this year, “Okay. 385 Black-owned businesses have been on-boarded onto the shelves of our pledge takers.’ So that’s real impact. We’re able to see those purchase orders. We know how many people work at all of these companies. We’re tracking all of that. And so I think continuing to take that survey and data and all of that really helps us understand that this mission is important. We are all looking at the road ahead and saying, “Wow, this journey is going to be long.”

We’re talking about racial justice, we’re talking about climate change. It seems like it’s insurmountable the distance that we have to go. And we don’t often take time to turn around and look at how far we come, which is oftentimes so much further than we would’ve ever expected. And we need to also give ourselves credit for that too. So I think taking time to applaud the progress that we’ve made and seeing those data sets gives us inspiration to continue pushing forward, even when it’s hard.

SAFIAN: You really are an optimist, aren’t you?

JAMES: I am, thank God, right? Otherwise, how would I be able to continue doing this work?

SAFIAN: You mentioned that not every retailer has embraced the 15 Percent Pledge. You mentioned Target. You were pretty vocal this spring when Target announced a commitment of a certain dollar amount, like $2 billion, which is a big number to Black-owned businesses by 2025, that that sort of wasn’t enough.

JAMES: Yeah. I mean, listen, if you are going to receive an ask from a nonprofit organization, which right now is being run by 15 women, predominantly women of color, right? And they’re asking you to make a commitment to the Black community and try to get to a goal of 15% shelf space, not overnight, right? We’re asking people to take time and do this in a thoughtful way that makes sense for, not just them, but also the Black-owned businesses. And it’s not meant to be a sprint, it’s meant to be a marathon, right?

So if you’re going to receive that ask, and if you’re going to decline, right, then I need to know what you are doing, right? And if you think that you have a better strategy at place, then please feel free to execute on that. But don’t try to massage the numbers or present things in a way that might be confusing, or just give us a headline. We really need to know and deserve to know the brass tacks of what the commitment is. And to be quite frank with you, Bob, I’m not that interested in press releases unless they are accompanied by some sort of external accountability partner. And that’s really what we are doing for our pledge takers. And we’re also, by the way, building a community of some of the most progressive and incredible companies in the United States of America that really want to figure out how to do this together.

And listen, I am grateful that Target is trying to do some work. And I still hope and suggest that they commit to the Pledge because I think that we could strengthen the work that they are doing. But nonetheless, they’re going to have to keep up with us. Even if people aren’t taking the Pledge, they’re taking the Pledge. That’s what they don’t realize.

SAFIAN: You mentioned the collaborative part of the Pledge. So not each organization is taking exactly the same pledge. Some pledge takers commit to featuring more Black-owned businesses in their marketing and editorial content. Some commit to improving their recruitment and hiring and retention of Black employees. Is that consistent across all the companies or each pledge is a little bit different?

JAMES: So the initial call-to-action was for major retailers. But as the Pledge started growing, pretty quickly we started realizing that in order to accomplish this mission of economic justice across the country, we were going to need a whole coalition. So American Vogue, for example, pledged with their representation. So now that we know there’s going to be more Black-owned businesses at retailers across the country, we also need to make sure that people know about those Black-owned businesses. So having media partners like InStyle magazine and Vogue magazine commit to featuring and storytelling around those brands was incredibly important.

Yelp, for example, took the 15% Pledge, and what they did that was insanely helpful to Black-business owners was creating that Black-business filter. So everyone in America is able to actually find the Black-owned businesses that are closest to them. So while Yelp didn’t have a traditional shelf space, they were able to look at what they did as a business and make sure that they were able to support the Black community in that way. And then also they have a lot of events and a lot of marketing, so making sure that 15% of that attention is also going to Black-owned businesses. Anyone that really wants to commit and take their existing business and figure out how to continue doing great business, but include Black people, and 15% of that is what we’re really looking for.

SAFIAN: In your collective impact survey said something about how some companies doubled their percentage of Black director-level-staff or above. So that’s another way a company can participate?

JAMES: What’s so interesting about the Pledge is it starts off as a shelf space proposition. But in order to actually get to 15% of shelf space, you actually end up having to address all of these other issues that are going on in your company. Because when I launched the Pledge, most of these retail … Well I want to say all, but I’ll just say most. They had no idea where they were actually at. From what we’ve seen, nobody was above three percent, and most retailers are one percent and below.

And so you then have to ask yourself how the heck did we get here? You realize, okay, your buying teams maybe have been the same for a really long time. They may also not be incentivized to be able to take a risk. How are you finding new brands? If you’re, like, only ever picking up the latest from Procter & Gamble, that’s probably not going to leave shelf space for you for Brooklyn Tea.

And so reall,y we needed to start looking at what representation was across corporate, what board representation looked like, what their relationship was with HBCUs. In most cases, there was no relationship. What they’re doing for recruitment, all of these different areas, and really start doing some of that repair work.

And listen, ultimately what I always say is that everyone, even myself included, is a little bit guilty, but ultimately the system is to blame. And so what we have to do now is take where we’re at and figure out how we do some course correction with this system, so we can sort of restructure it in a way that creates a world that is a little bit more equitable for all of us.

SAFIAN: And you’re also, in the process of this fostering the other side of the marketplace, helping Black-owned businesses directly. I know you just announced a new partnership with Google to help on that front.

JAMES: Yeah. So we have a business equity community that I’m so excited about, which is a whole coalition of over 1,200 Black-owned businesses across the country right now. They are some of the most promising I think in the world. And we’re really getting on the phone and having conversations and dialogue with each and every one of them to figure out how we can be most supportive and continue getting resources their way, so that we can actually see them scale into the next crop of unicorns and IPOs. And really that is the proposition of the Pledge. It’s about supporting Black-owned businesses and advocating for Black entrepreneurs and Black future founders.

SAFIAN: Google helped us build the database. And they’re also providing resources to us and working with us to create workshops and activations and programs in order to, A, help these entrepreneurs build community. But B, have more access to the tools and information that they’re going to need. I’m an entrepreneur myself. I started my company, Brother Vellies, with $3,500 at the Hester Street Fair on the Lower East Side. Don’t know if you’ve ever been there, Bob, but it’s definitely not Barneys.

I definitely didn’t have friends and family that I would be able to take money from to pay for my first purchase order. And a lot of Black-owned businesses have very extreme lack of access to capital. And so we need to help them figure out how to get the resources that they need, how to even negotiate the contracts that they’re receiving, all of these things. So it’s not just about giving a company a purchase order and being like, “Okay, here you go. Make it work. Grow your company.” It’s about giving them the tools and the mentorship and the access to actually be successful at the proposition.

SAFIAN: Before the break we heard Aurora James explain how the 15 Percent Pledge came into being, and how an entrepreneurial playbook unlocked $10 billion worth of impact for Black-owned businesses.

Now Aurora shares how her own business, Brother Vellies, pivoted in the pandemic at a moment of desperation, in a way that actually improved the model and expanded her customer community.

Aurora also talks about how she relies on optimism to help get through the toughest moments,

and why even when brands decline to partner with the 15 Percent Pledge, she can still have impact in pushing them along.

And she makes a direct plea to the Masters of Scale audience about how together we can all do more.

So I want to ask you a little more about Brother Vellies because it’s also focused on an inclusive and equitable approach.

JAMES: People that know me really can see that very clear parallel. Oh, the 15% Pledge actually is Brother Vellies in a different manifestation. So for everyone listening that doesn’t know, Brother Vellies is my accessories brand. And I started it in January 2013 with the goal of preserving and growing traditional artisanal skills across Africa. So I started with a shoe called a vellie, which is a traditional Southern African, mainly South African Namibia shoe. And when British people were in South Africa many moons ago, they happened upon this traditional shoe shape and brought it back up to England and created a company that we know today called Clarks. And they renamed it a desert boot, but it is actually a traditional South African shoe called a vellie.

And so I created my company just based on that shoe shape and trying to save the shoe workshops that were in Southern Africa that were making that shoe that were just folding rapidly. And I grew and scaled that business by myself, which was incredibly difficult. I hit all of the roadblocks. I’m still here today. And I was able to end up supporting a number of different artisans across the world. We’ve worked in South Africa, Kenya, Morocco, Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Mali, Bali, Haiti, Italy, Mexico, Canada, and America. And it’s been a really wonderful, beautiful, exciting project. And I’ve been able to grow my company and sell millions of dollars worth of shoes and handbags and that’s been really incredible.

SAFIAN: You could have said, “Oh, I love those styles. I’m going to manufacture them wherever.” You made the conscious choice that you wanted to preserve and expand not just the designs, but the system and the artisans and the communities where these, sort of, traditional goods were made. And this now extends across lots of different communities.

JAMES: Every single investor that I met with early on was like, “Oh wow, these shoes are really amazing. Would you consider making these in China? I mean, you would get such better margins.” And that really wasn’t what it was about. But to give you an example, we work with a couple of workshops in Mexico making a traditional Mexican huarache, which is a really wonderful, woven, flat shoe.

I worked with them a little bit, altered the pattern, sort of used slightly different materials. When Meghan Markle started wearing our Huaraches a couple of summers ago, right before the pandemic, not only did we sell out, all of the artisans basically who were making huaraches and selling them sold out.

For me, that’s really what it’s about, because with Brother Vellies, because of the way that we’re sourcing our materials, a lot of it’s sustainable and animal byproduct, it ends up being a slightly more expensive product. Our Huaraches, I think, are $230 to $260.

That’s more than what you would buy a Huarache for just on the street in Mexico. But when we actually look at the labor that goes into making those shoes and what it costs to actually pay people fairly for their work, it ends up being quite expensive. When we break down the margins on some of what is made artisanally and sold in the marketplace, we realize that it’s actually not sustainable for people to be working for those prices. When we take these traditional shapes and put them in a luxury space and pay and train artisans appropriately, what we hope we’re doing is raising the bar for what they can expect to be paid from outside communities for their work.

SAFIAN: You’ve got a store in Brooklyn, though most of the sales are online. As you say, you work with these artisans all over the place. How was that process and that part of the business impacted by the pandemic? I can imagine that you had some disruption.

JAMES: We had big disruption. People definitely were not trying to buy shoes, let alone like heels or anything like that, handbags during a global pandemic when we were all staying inside.

For me, first and foremost, I was just concerned about the artisan communities and the staff that worked for me. We really pivoted most of our workshops to start making masks, because in many situations we were kind of the only people with sewing machines in the community. Our dust bags that we often sell the shoes in, we were using those fabrics to make masks.

Then in terms of getting the materials that they needed to be able to make shoes, I mean that really wasn’t happening. II had a couple thousand artisans who were looking at an uncertain future. I had a business that was also suffering, and I sort of put the three things together, and we were able to create a program called “Something Special,” which is actually a subscription model where we used what was locally available to our artisans to create small home goods.

The first thing that we did, for example, was a mug that was made by a female collective in Oaxaca that were all quarantining together. My customers subscribe to this subscription program, so we were able to sort of work with all of our different artisan groups and say, “Okay, this is what we can make together.”

We had carvers in Kenya that were making special things. It’s been really beautiful to be able to support different artisans and makers. And at the same time, bring these really special, thoughtful things into the homes of my customers for $35 a month.

It’s a really great way for communities to support each other through a really difficult time. I’m really proud of that program. It was a great pivot for Brother Vellies to make during the pandemic.

SAFIAN: It’s like it’s a completely different business though, right?

JAMES: Completely different business. Right before the pandemic in January of 2020, our average order value online was $680. Five months after the pandemic, it was $79. Totally different business.

We were going from mailing shoes to people to mailing thousands of mugs. It was a tough pivot, but it was a necessary pivot. And my gosh, how grateful am I that we were able to do something like that instead of just folding like 40% of the other Black-owned businesses across this country. I’m so grateful for that.

SAFIAN: Is this going to continue to be part of your business?

JAMES: Absolutely. It’s going to continue to be a part of it, because it’s a really, really, really incredible way for us to support all sorts of different artisans across the world. We’re already working on a fan, like a hand-woven hand-fan for June of next year that’s being made in Kenya.

We’re using grasses, and we’re using wood. There’s farmers that are being supported. Then there’s weavers, and there’s carvers just in one product.

Then it brings my customers so much joy because listen, I have what, a quarter million followers on Instagram.

Rest assured that all of those people cannot afford to buy luxury shoes. Having an opportunity for them to be able to be involved in Brother Vellies and what we’re doing for $35 a month is also incredibly important to me and has been one of the greatest joys of the pandemic. I don’t want to leave them out of our community based on what they’re able to afford.

SAFIAN: You mentioned at the very beginning that just before the start of the 15 Percent Pledge, you were getting lots of calls from people in business and retail and elsewhere coming to you for context and perspective. “You run a Black-owned business. What can we do to help foster the community?” I can imagine those questions have not diminished. Does that burden get tiring for you?

JAMES: Yes. I would be lying if I didn’t tell you that it’s really, really hard. For all of the companies that have taken the Pledge – Ulta Beauty, Rent the Runway, CB2, Hudson’s Bay – there are a lot of other companies that haven’t taken the Pledge. Some of those companies I’ve spent countless hours on the phone with talking to CEOs or chief merchant officers or people who just don’t think that they can do it, or they’re afraid to fail.

What they don’t realize is that they’re actually already failing. The inability to commit to actively trying to make that sort of difference is the fail. Sometimes we get so paralyzed by the magnitude of what it feels like to be the problem that we can’t even act at all.

I think for me, some of those conversations are so tough because I know what kind of impact they can have. Listen, when I first launched the Pledge, it was pretty confrontational. Anyone that knows me knows that I’m not a confrontational person. But on social media, I’m like, “I need you to do this. You have to do this.” It was very aggressive.

The people that have relationships with me know what my heart is and know that I’m incredibly collaborative. I was raised in a household where there were a lot of really wildly different opinions. My father was born and raised in Africa. My mom is white. She was adopted at birth. I was raised a lot by my grandmother.

We’ve had to have a lot of tough conversations over the dinner table. There’s nothing that anyone can say that can surprise me.

But Bob, I will tell you, it is tough to talk about racial justice every single day. Sometimes I just wish that I could sit down at a dinner and have someone turn to me and be like, “Did you see that Britney Spears Instagram post?” That’s not the conversation that people are having with me right now. It tends to be a little bit heavier stuff, but it’s okay, I’m here for it.

SAFIAN: What’s at stake in this moment right now?

JAMES: Everything’s at stake. This time is so incredibly critical for all of us. We’re dealing with racial justice. We’re dealing with climate change, which is also racial justice issue.

There’s a ton of green-washing that’s happening. Disinformation is rampant. The kids are having a tough time knowing who to trust, where to get their information from.

They’re suffering from anxiety and depression. We’re all spending increasing time on social media, which we know is horrible for our health. We are all also being pitted against each other at every possible opportunity. It’s like a divide-and-conquer.

We have to coalesce as humans and have tough conversations in community and promise each other that we’re going to do our best.

SAFIAN: Despite all those challenges, you are optimistic. Where does the optimism come from?

JAMES: I mean, listen, everyone has told me my whole life that things were going to be impossible. “That’s not possible. This isn’t possible. It’s never going to happen.” I’m constantly surprised by how wrong people are when they say never and impossible.

If I had called a whole bunch of people before I decided to post my Pledge ask a on Instagram, everyone would’ve told me I was out of my mind. They would’ve been like, “There’s no way that LVMH is going to agree to let Sephora change 15% of their merchandising.” Sephora Canada, by the way, Bob, pledged 25% of their shelf space going to BIPOC owned businesses, 25%. I mean, we’re literally completely changing what that store looks like. People would’ve told me I was out of my mind, and we’re doing it. It’s happening. Guess what? It’s incredible business for them.

All of our pledge takers are coming back to us saying, like, “Not only was this the right thing to do, it’s also like one of the best business decisions we’ve ever made, and it’s been incredible for team-building.”

What I know is the power of the people, and when people are passionate about something, they are relentless in that pursuit. What we need to do is get each other inspired and get each other feeling passionate about creating actual positive change because when we do that, the change will happen and we see it. We see these glimmers of moments of hope where these incredible things happen that give us chills.

SAFIAN: Well, I love your energy. I applaud your optimism because I do think we need more of it. And like you, I believe that optimism does unlock incredible potential. Our audience are a lot of business owners and business people. Is there anything you would say directly to them about the 15% Pledge, about what you’re doing?

JAMES: I mean, to anyone listening, I think it’s really easy to say, “Wow, the 15% Pledge, that sounds great, and I’m so happy these other companies are doing it.” But ultimately there is a way for every single company to commit to the 15% Pledge, whether it’s in your B2B, whether it’s in your shelf space, whether it’s in your pages, whether it’s in your financials in another way.

I have every kind of idea about how Silicon Valley can take the Pledge. Literally everyone can take the Pledge. We’ve been working with a ton of companies as well to figure out what that pledge-taking can look like and how we can continue to support this ecosystem and really change the landscape of America’s economy and make it a little bit more equitable for everybody.

SAFIAN: Aurora, thank you so much for doing this. I really appreciate it. I do hope people do keep coming your way.

JAMES: Thank you so much, Bob. Thank you for having me.